|

In the face of intensifying weather patterns like the series of storms pounding the West, regenerative organic farms are demonstrating that the key to resilience is working with nature. As California experiences a historic succession of winter storms, most of us will see extensive reporting on power outages, flooding, and mudslides. But amidst the destruction, there is a story of resilience and preparedness that will get less attention. A small but growing contingent of farmers is poised to not only rebound from the deluge of water, but to benefit from it. These farmers have a valuable lesson to share: ecologically-minded, regenerative organic agriculture that prioritizes soil health is critical to our future. In a region parched by megadrought and greatly affected by human alteration, the landscape cannot absorb rapid, uninterrupted rainfall. Agriculture has overworked much of this state—heavy tillage, lack of crop diversity, and agrochemical use have turned living, absorptive soils into easily eroded dirt. We have also redirected rivers and waterways that once transected the landscape and built on top of floodplains. And through clearcutting and the deprivation of healthy fire cycles, we have destroyed our forests’ natural adaptation to heavy precipitation. Despite our desperate need for this water, we have greatly diminished our ability to receive it. This is particularly bad news in a state that produces over two-thirds of the nation’s fruits and nuts and one-third of its vegetables. Though they are suffering from prolonged water scarcity, most of the farms here will see limited direct benefits to their land from the atmospheric rivers hitting the state this season. Many will also suffer crop losses as their fields are flooded and crops in compacted soils drown. And, come summer, they will likely be back to overpumping underground aquifers and overreliance on surface water (as the Sierra snowpack is now melting earlier than it once did). I teach professionals from all backgrounds about regenerative agriculture through experiential education and the farmers I work with are excited about capturing a significant share of this rain on their land. Of course, they would prefer that it come more gently and not all at once, but that is not the reality here. Elizabeth and Paul Kaiser at Singing Frogs Farm in Sonoma County, widely known for their leadership in ecological farming, have seen their lower lying fields flood 11 out of the last 15 winters due to the hydrology of their land. But instead of causing serious damage, their regenerative methods mean that “the water that hits [their] farm goes into the soil and ground below,” says Elizabeth. That’s because their organic no-till practices, regular compost applications, and diverse crop rotations have added a significant amount of organic matter to the soil, causing it to act as a sponge that absorbs water faster and retains it for longer. So, despite the fact that the soil has taken in over 13 inches since December 26th, Elizabeth says they have been able to start planting their spring crops. Paicines Ranch, further south in San Benito County, is another leader in regenerative agriculture. Paicines integrates livestock into their vineyards year-round in imitation of natural ecosystems, cultivates biodiversity, and also avoids tilling. Paicines has experienced “no runoff from our vineyard since we began managing it regeneratively in 2017, despite being situated atop a hill, and I am eager to see how our soils perform with more rain coming,” said Kelly Mulville, the ranch’s vineyard director. “The vineyard soils are now capable of holding all the water this past series of storms has poured on it.” (Disclosure: The owner of Paicines Ranch is a financial supporter of Civil Eats.) Regenerative organic farmers understand that extreme weather patterns are not novel. California’s history is one of drought, flood, and fire that cannot be conquered. Nor should they be; these forces have shaped an abundant landscape, one which has supported human civilization for millennia. But as climate change increases the severity and variability of these forces, adaptation is as important as ever. Ecologically minded farmers are keen observers of nature. Instead of fighting against it, they harness its natural processes to grow food. Instead of simplifying landscapes, they cultivate biodiversity above and belowground, which creates resilience. The healthy soils on these farms are full of life and decaying matter, commonly referred to as soil organic matter. This life creates soil pores (up to 50 percent of total soil volume) and glues particles together, allowing water to infiltrate rapidly without washing it away or drowning plants. Source: Ryan's Peterson article from Civil Eats Olive tree growing deals with a tree of great historical, economic and environmental importance, which is why it is deeply rooted in the traditional habits of every producer. The organic cultivation of olive tree is based on methods of rejuvenation of the olive tree grove soil, the recycling of by-products and other available organic materials and the reproduction and protection of the natural environment. It is the method of olive production that aims to produce an excellent quality olive oil (meaning extra virgin olive oil), free from pesticide residues, which undermine health, and reduces contamination of soil, water and air. It also contributes to the preservation of the diversity of valuable plants of the area, wild animals and genetic material of the olive tree. Creation of an organic olive tree grove Suitable location: Before creating or setting up a new organic olive tree grove, it is necessary to study and take into account the soil-climatic conditions of the area. Locations with limited sunshine, long periods of shading and frost-affected areas should be avoided as much as possible. Coastal areas and areas with cool weather and high relative humidity, especially during the summer and autumn months, should not be preferred, because such areas favour high infestations from Olive fruit fly (Thakos (Δάκος) in Greek). It is also very important the principle that the location where the organic crop will be planted should not be affected or neighboured by conventional olive groves. In a sloping location protection measures must be taken against the transfer of rainwater from conventional olive groves or other conventional crops. Also, if possible, the plantation should be isolated with a tall natural windbreaker, so that it is not affected by spraying that will be carried out in conventional olive groves or other crops. Selection of soils and measures for their correction The main concern of every olive tree grower is from the beginning of the conversion or planting of the organic olive grove to do all those actions to significantly improve the physical and chemical properties of the soil for normal nutrition and growth of trees. We must keep in mind that the soil is a living organism with a number of important biological processes that in turn can feed the olive trees. Heavily used and damaged soils, with a limited concentration of organic matter, do not help the olive trees to grow and perform satisfactorily. Boring and cohesive soils that retain enough moisture cause rotting in olive trees and reduce or inhibit the prevention of various nutrients. Soils poor in organic matter are corrected, either by adding organic matter or animal manure or by applying green fertilizer, which is done by incorporating in the soil a mixture of legumes (vetch, broad beans, peas, etc.) with grass plants, with the aim of increasing organic matter and nitrogen. Green manure is the cheapest method due to the advantages it provides both to the ecological system (non-dependence on the imported expensive system of organic matter), but also in terms of cultivation (competition with some weeds, etc.). Also, the addition of organic matter to the soil improves its structure, makes it easier to cultivate the soil from agricultural machinery and allows better absorption and retention of moisture. Olive grove installation and varieties The olive trees of the organic olive grove must be planted at regular distances. Dense planting does not help their normal ventilation. In sparse planting, the entire area of the land is not economically exploited. Olive trees are preferred to have a trunk of normal height to facilitate the necessary cultivation care and normal ventilation. The most suitable varieties for organic farming are considered to be those that are resistant to pests and diseases and are adapted to the soil-climatic conditions of each region. Varieties grafted on wild olives show resistance to soil diseases and develop a large root system. The olive varieties 'Koroneiki', 'Ladoelia' and secondarily 'Picual' show considerable resistance to enemies and diseases. Cultivation care Nutritional requirements of olive trees: Significant amounts of the main nutrients of nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium are removed from the olive grove every year due to the needs of the plant for vegetative growth and production. It is natural that when the quantities removed are greater than those available there will be a reduction in production unless these elements are supplemented. The amount of elements to be added to the soil of each olive grove depends on the type of soil, the available stocks, the cultivation practice followed (pruning, irrigation, etc.) and the production of the year. Consequently, it is not possible for anyone to come up with an ideal fertilisation strategy that applies to all conditions, but it can single out some general guidelines. The most important parameter is always the nutritional requirements of the crop, in this case the olive. The first concern is to replenish at least the nutrients removed by harvesting and pruning. It has been found that on average 100 kg of olives remove from the soil: 0.9 kg Nitrogen (N), 0.2 kg Phosphorus (P), 1.0 kg Potassium (K) and 0.4 kg Calcium (Ca). An amount of nutrients that are trapped in the soil, in non-digestible form (mainly in Phosphorus and Potassium) or even lost by rinsing to the lower layers of the soil, mainly in Nitrogen, must be taken into account. Fertilization methods The fertilization of the organic olive grove aims at the improvement of the soil productivity and the strategy that ensures long-term improvement of the texture and structure of the soil along with the increase of its fertility. Olive fertilization should be based on a program to maintain and rejuvenate the soil of the olive groves. This program is mainly based on the application of the method of green fertilization with legumes, grasses or mixtures, the addition of compost from organic materials, as well as the addition of animal manure, which necessarily comes from animals primarily organic or even extensive breeding. Organic fertilization: An economical and practical way of fertilizing the organic olive grove is the preparation of compote using the plant residues of the olive grove with manure from organically or extensively farmed animals. One way to make organic compote is to use olive leaves from olive mills along with about 10-20% of sheep and goat manure. The construction of this type of organic compote costs money, so it is usually used in the first 3-4 years of conversion of the olive grove into organic. In the following years, olive leaves and other plant residues can be used together with 20-40% oil extracts from the tanks of the oil mills. It is well known that mill waste has a good content of various nutrients, organic matter and microorganisms. The best time to place the compote is immediately after harvest. For every tenth, an average of 2 cubic meters of compost is recommended. The fertilization is supplemented with the integration of the natural vegetation of the olive grove, with the integration of the leaves and branches up to 5 cm thick that are crushed by the cultivation, with the use of special mechanical tools-crushers, as well as with the use of the effluents of the olive mills. Part of this article can be found on gargalianoionline.gr (News from Messinia on time) Most of us think of gardens as sunny places, which is likely due to the fact that the crops we're used to growing and eating require full sun to thrive. And it's true: those summer veggie gardens brimming with squash, green beans, and tomatoes require a lot of sunlight. Many edible plants, on the other hand, can grow in the shade.For those of us who want to grow more of what we eat, it's critical to understand what we can grow in less-than-sunny conditions. A variety of fruits and vegetables, it turns out, prefers shade, or at least dappled shade, to do their thing. If being experimental and adventurous, with a dash of self-sufficiency, sounds like a good time, the list of shade-tolerant produce below might be just what you're looking for. 1. Ostrich Fern: Every spring, the forest floor is littered with new plant sprouts that have been waiting for some warmth. Ostrich ferns produce an abundance of edible fiddleheads (unfurled fronds) that are similar to asparagus for those in the know. They prefer partially shady locations and grow into lovely ornamental plants for the rest of the year. 2. Ramps: Ramps, also known as wild garlic, grow naturally in deciduous forests where the soil is rich in organic matter. They are spring ephemerals that prefer to bask in the sun before the trees' leaves have returned. Ramps take a while to get going (a few years before harvest), but they are perennials that can produce tasty greens for many years. 3. Creeping Raspberry: Creeping raspberry (thimbleberry) grows low and prolifically in shady areas, such as the understory of food forests, and makes an excellent edible. It produces delicate fruits that are too soft for market transportation. Nonetheless, they have a flavor similar to raspberries and make delicious jams. They prefer full shade. Another advantage is that they are thornless. 4. Wintergreen: Wintergreen is a low-growing evergreen that makes a lovely groundcover and has edible berries and tea-making leaves. Wintergreen's flavor is derived from both the berries and the leaves, as the name implies. This is an excellent groundcover for shady gardens. They can tolerate some sunlight but prefer to be in the shade. 5. Sweet Cecily: Sweet Cecily, a self-seeding member of the carrot family, will quickly spread wherever it is planted. It thrives in partial shade and produces a delicious variety of snacks, as well as attracting a large number of pollinators. Sweet Cecily, like many other wildflowers, prefers to be planted in the fall and will bloom the following spring. Grow 7 food plants in shaded areas6. Arctic Beauty Kiwi When we can grow something vertically, even in shady areas, we save valuable growing space. Arctic Beauty Kiwi thrives in partial shade. It grows to be about 10-12 feet tall and produces divine fruit that resembles hardy kiwis (smooth and green on the outside) rather than the fuzzy kiwis found in supermarkets. 7. Elderberry: Elderberry trees are voracious, quick-growing plants that thrive in wet soil and partial shade. Both the berries and the flowers are medicinal and edible. In general, the berries are used to make jam, syrup, and wine. Teas can be made from flowers. If the trees become too large, they can be pruned and will recover to continue producing. Grow a lot of food in areas that most gardeners believe are off-limits to plants. That is not the case at all. Lots of tasty foods will grow in places where the sun rarely shines.

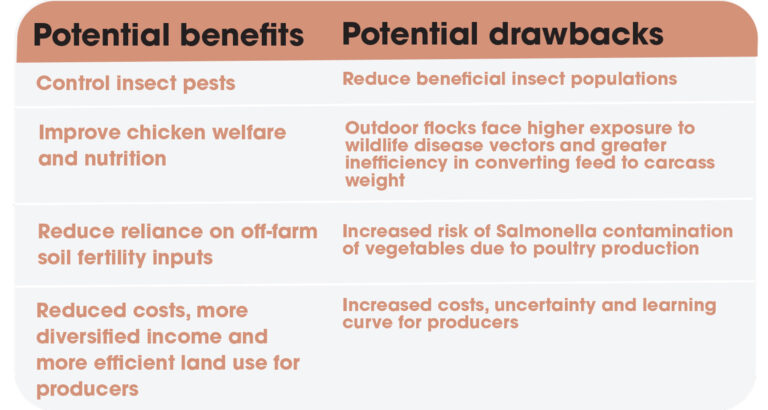

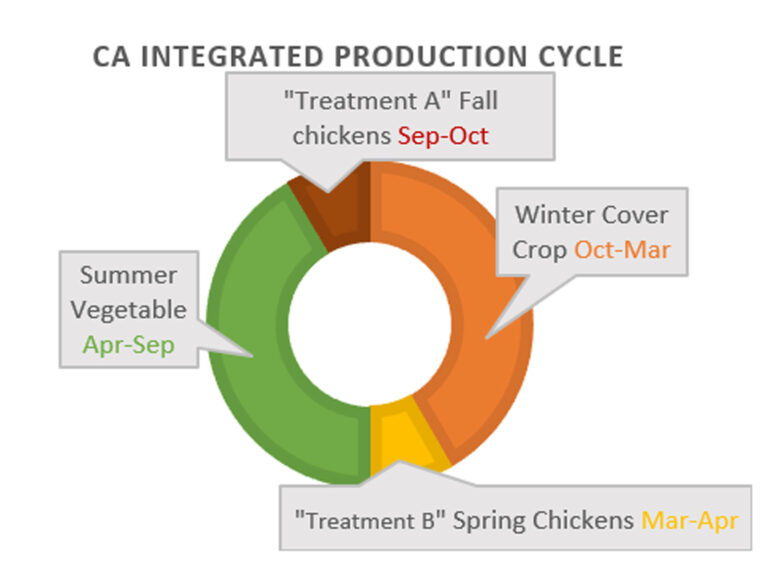

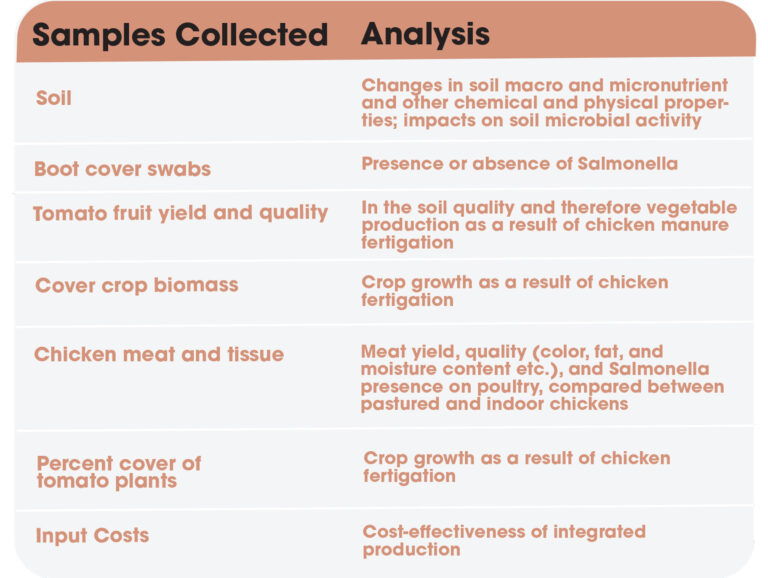

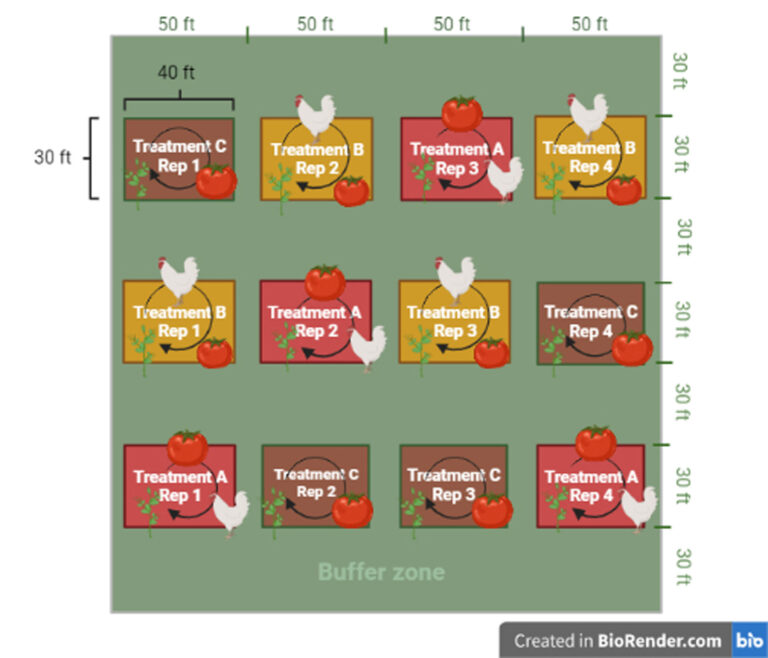

Integrating Chicken and Vegetable Production in Organic Farming Chicken and tomatoes are a tasty duo beloved by many in popular dishes like chicken tikka masala and chicken cacciatore. This combination, delightful in the culinary sense, is also the subject of a recent integrated farming experiment. This fall, researchers at UC Davis harvested the first crop of tomatoes from a 1-acre experimental field and successfully processed the second flock of 130 broiler chickens. This acre is part of a tri-state experiment also taking place at University of Kentucky and Iowa State University, where the experiment was originally spearheaded by horticulture professor Ajay Nair. Funded by USDA, this research aims to produce science-based learnings and best practices for organic agricultural systems that integrate rotational production of crop and poultry together on the same land. Potential of Integrated Production While the idea of chickens alongside crops evokes an image of “traditional farming”, these systems are relatively rare in North America today. Integrated farms have the potential to help organic farmers create a more resource-efficient “closed-loop” system. For vegetable farmers looking to start an integrated system, chickens require the lowest startup costs as compared with other livestock. This type of diversified production may be especially promising given the growing consumer demand for more sustainably and humanely produced chicken. However, there are many beliefs that remain unconfirmed and questions that remain unanswered by scientific research when it comes to integrating poultry production into vegetable cropping. For instance, at what extent does manure deposited by poultry on the farm reduce the need for off-farm soil fertility inputs? What benefits can we observe when crop residue is used to supplement the diets of the chickens? What stocking rate is the most advantageous in these systems? What types of crops and breeds of chicken work the best with poultry production in different regions? And is it feasible to squeeze in a successful yield of broiler production into the transition window between different crop seasons? Finally, can all this be done effectively from a food safety perspective and economically from both a farmer and consumer level? Study Design To better understand and evaluate the potential to integrate poultry with crop farming from multiple perspectives, the research objectives focused on evaluating growth yields, quality of agricultural outputs, food safety risks, agroecological impacts on soil and pests, and economic feasibility of such systems. In this experiment, broilers were raised on pasture starting at around 4 weeks of age to graze on crop residue. In the California iteration of this experiment, we raised two flocks per year in between rotations of vegetable crops in the summer and cover crops in the winter (Figure 1a). Rather than remaining in a fixed location, the pastured broilers are stocked in mobile chicken coops, commonly referred to as “chicken tractors”, which are moved to a fresh plot of land every day for rotational grazing. Four subplots distributed across the field are grazed by chickens before vegetables are planted in the spring (treatment B), and four different subplots are grazed by chickens after vegetable harvest (treatment A). The impacts of grazing on soil and crop production of the two treatments are compared to a third control treatment of only cover crops and vegetables (treatment C), while the impacts of rotational grazing on meat production are compared to an indoor control flock. Collaborating researchers in Iowa and Kentucky are also collecting weed and insect diversity data to better understand the impacts on crop pests and better understand how poultry affect the integrated farmland. Additional studies on animal welfare for the chickens as well as conducting cultivar trials on the success of varieties of different vegetables like lettuce, Brussels sprouts, butternut squash and spinach tested in combination with poultry are being conducted. Challenges Identified and Lessons Learned As the study is still underway, we cannot make any conclusions without testing and re-testing experimental results to confirm their repeatability and statistical significance across more than one growing season. So far, however, we’ve collected a great deal of initial learnings on our integrated systems. Soil Fertility Organic farmers know that soil amendments, such as chicken manure, release nitrogen slowly to crops over time. Factors related to timing of application, precipitation and temperature affect how soil microbes process organic material to ultimately impact the soil quality. In California, although our tomato crop received sufficient subsurface drip irrigation, we suffered low yield and tomato end rot across the treatments. This was due to the fact that our experimental plot was previously conventionally managed and very nutrient depleted, an issue which we attempted to manage by applying organic compost and liquid fertilizer to the entire field to supplement the manure deposited by the chickens. In addition, severe drought during and after the period of manure deposition may have hindered soil microbial activity and, in turn, retarded the decomposition of our cover crop residue and chicken manure into the soil. Meat Production Additional data remains to be collected on subsequent flocks and statistical analysis on the findings have yet to be conducted before conclusions can be drawn. Preliminary results from meat quality analysis indicate that the pasture-raised chicken yielded less drumstick meat than the indoor control and breast meat was darker and less yellow in color. They also yielded redder thigh meat and less moist breast meat than the indoor chicken when cooked. So far, broilers in California that grazed on cover crops in the spring reached a higher average market weight relative to indoor control, while broilers grazed on tomato crop residue in the fall reached a lower average market weight relative to the indoor control. Food Safety No presence of Salmonella has been detected thus far in the soil nor on the poultry produced in the California experiment. Collaborators in Iowa and Kentucky report that persistence of Salmonella associated with the poultry producing soil has not been observed to persist into the harvest period. While these results are promising, it should be noted that Salmonella are relatively common in poultry. Ideally, best practices can be identified that reduce the risk of Salmonella persisting in the soil environment while crops are grown following chicken grazing. Many other anecdotal findings have emerged: In Iowa, a farmer collaborating with researchers to conduct their own on-farm iteration of the experiment has noted positive results from the poultry treatment on their spinach crop; our collaborating researchers also report that the chickens may appear to be eating an insect that is beneficial in their agricultural system, a finding which, if validated, may debunk the perception that their presence on the farm is always advantageous to pest control. In California, we are realizing the impact the design of the chicken tractors has on labor demands. Our 5 x 10 ft-wide wheeled coop was more difficult to move in a tomato production system with raised beds and loose soil as compared to a relatively more even and firm ground in a pasture. It seems apparent that engineering considerations such as wheel type, coop material and coop weight will influence the adaptability of poultry and crop integrations. Careful timing and planning is yet another labor consideration when it comes to transitioning successfully between cropping and poultry husbandry that we encountered. Eagerly, we await to gather more information in the next year until additional conclusions to our research questions can be drawn after the study concludes in 2022.

Additional Resources Nair, A. & Bilenky, M., (2019) “Integrating Vegetable and Poultry Production for Sustainable Organic Cropping Systems”, Iowa State University Research and Demonstration Farms Progress Reports 2018(1). Source: Organic Farmer Magazine Here in FOS Squared we believe that there is no climate change as this is defined by politicians to serve interests of global funds instead there is serious enviromental pollution and contamination including underground waters, sea, soil, mountains, tree, animals literally everything caused by the interests of corporate companies supported by corrupted politicians across the globe Combined stressors could impair soils’ ability to cycle nutrients and trap carbon Source: Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies Summary: Community ecologists investigated the interactive effects of rising temperatures and a common livestock antibiotic on soil microbes. The research team found that heat and antibiotics disrupt soil microbial communities -- degrading soil microbe efficiency, resilience to future stress, and ability to trap carbon. Soils are home to diverse microbial communities that cycle nutrients, support agriculture, and trap carbon -- an important service for climate mitigation. Globally, around 80% of Earth's terrestrial carbon stores are found in soils. Due to climate warming and other human activities that affect soil microorganisms, this important carbon sink is at risk. A new study led by Jane Lucas, a community ecologist at Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies, investigated the interactive effects of rising temperatures and a common livestock antibiotic on soil microbes. The research team found that heat and antibiotics disrupt soil microbial communities -- degrading soil microbe efficiency, resilience to future stress, and ability to trap carbon. The work, now available online, will appear in the December issue of Soil Biology and Biochemistry. Lucas, says, "Most studies of soil health examine only one stressor at a time. Here, we wanted to explore the effects of warming temperatures and antibiotics simultaneously, to get a sense of how two increasing stressors impact soils." Monensin was selected because it is a common antibiotic whose use is expanding on cattle farms. Monensin is inexpensive, easy to administer, does not require a veterinary feed directive, and is not used in human medications. Like many antibiotics, Monensin is poorly metabolised; much of the antibiotic is still biologically active when it enters the environment through animal waste. The team collected samples of prairie soil from preserved land in northern Idaho that was free of grazing livestock. Vegetation cover at the collection site, primarily tallgrass prairie, represents typical livestock pasture -- without inputs from cattle waste. Soil samples were treated with either a high dose, low dose, or no dose of the antibiotic; these were heated at three different temperatures and left to incubate for 21 days. Temperatures tested (15, 20, and 30°C) represented seasonal variation plus a future warming projection. For each treatment, the team monitored soil respiration, acidity, microbial community composition and function, carbon and nitrogen cycling, and interactions among microbes. They found that with rising heat and antibiotic additions, bacteria collapsed, allowing fungi to dominate and homogenize -- resulting in fewer total microbes and less microbial diversity overall. Antibiotics alone increased bioavailable carbon and reduced microbial efficiency. Rising temperatures alone increased soil respiration and dissolved organic carbon. Increases in these labile carbon pools can lead to a reduction in long-term carbon storage capacity. Lucas says, "We saw real changes in soil microbe communities in both the low and high-dose additions. Rising temperature exacerbated these antibiotic effects, with distinct microbial communities emerging at each temperature tested. Within these assemblages, we saw reduced diversity and fewer microorganisms overall. These changes could diminish soils' resilience to future stress. We also found that heat and antibiotics increased microbial respiration, decreasing efficiency. Essentially, microbes have to work harder to survive when they are in a hot, antibiotic laden environment. This is similar to how it is easier to walk a mile when it is 70 degrees than it is to run a mile when it is 95 degrees. Decreased microbial efficiency can cause soils to store less carbon in the long term." As soil microbes are working harder (and inefficiently) to process carbon, less is converted into a stable organic form, which would become trapped in the soil. Instead, more carbon dioxide is released into the atmosphere as a gas. This effect could turn an important carbon sink into a carbon source, exacerbating climate change effects. Senior author Michael Strickland, an Associate Professor at the University of Idaho's Soil and Water Systems Department, says, "Forces of environmental change do not play out in isolation. Our results show that heat alone, antibiotics alone, and heat and antibiotics together all have different effects on soil microbial communities. These findings highlight the importance of testing multiple stressors simultaneously to more fully understand how our soils, and the essential functions they perform, are changing." Lucas concludes, "This work aligns with the 'One Health' approach. Agriculture, the environment, and public health are inextricably linked. Understanding how multiple stressors shape soil microbes is critical to supporting soil health in the face of global change. If we do not manage for interactive effects, things like soil carbon storage capacity and crop production could be jeopardized. In addition to broader climate mitigation efforts, limiting antibiotic inputs to the environment could help protect soils." Article Source: Science Daily Photo Source: Andrea Lightfoot-Unsplash (Code: GX6be6LLIR4) Farmer Angus McIntosh has the intense look of someone with a single dream like skateboarding to the South Pole. He wears a slightly ingenuous expression, as if he has just been born into a new world and finds everything curious and a bit disturbing. With a background as a trader for [...........] in London, there is a hint of cufflinks and striped shirt in his farmerish attire and smooth talk. However, his verbal spritz no longer sprouts derivatives and hedge funds but involves a passion for environmentally friendly farming. And boy do you need passion. In a world where farming is a big industry (visiting a farm in the USA is hazardous because of free floating poisons), following a dream of clean food is a kind of madness. Farmer Angus’ farm is situated on 126 hectares of irrigated pasture at Spier Wine Estate near Stellenbosch. It is a place that ignites the heart with its well cared for animals, green pastures, vegetable gardens and on site butchery. A friend calls it “fairyland”. The farm arguably hosts the Cape’s best non-industrial food production. The eggs are yolky and delicious and the meat which can be ordered online is clean and tastes like meat used to taste. Remember? Before feedlots, pesticides and hormones. About six years ago I discovered his eggs by chance, astonished by their creamy innards and thick marigold coloured yokes. Investigating their origin, I came across Farmer Angus, moving his egg laying hens in “eggmobiles” to new outdoor pasture. He told me then, “The biggest lie in agriculture is free range eggs. They live in barns, they don’t range outside. On commercial egg farms, chickens live and never leave a space equivalent to an A4 piece of paper.” And it is not only the animals that are benefitting. His egg company is now 80% owned by his staff and the eggs get better and better. “I am only a 15% shareholder but it’s got my name on it,” he says. Over the years McIntosh has developed biodynamic and regenerative agricultural practices in the raising of the farm’s animals which include cattle, pigs, chickens and laying hens, as well as vegetables and wine. His pastured livestock and poultry are moved frequently to new pastures where they can perform basic needs such as dustbathing and flapping their wings. Often in the past in butcheries or so-called organic groceries, I have asked about provenance. So far I have never met a retailer who has even taken the trouble to see where the food (particularly labelled as “organic”) they sell comes from. Farmer Angus encourages people to visit the farm and see where their food is produced. Caring for the animals properly is a high priority. More and more restaurant owners around the world are keeping their own herds for the simple reason that cared for cattle produces not only the healthiest but the tastiest meat. With farming there is so much wonkery – what irony that the salt of the earth, the food we eat is as about as full of corruption as the Zuma Cabinet. His desire is for people from all walks of life to be able to eat better and more nutritiously and to understand what they put in their bodies. [...................] The challenge of agricultural sustainability has become more intense in recent years with climate change, water scarcity, degradation of ecosystem services and biodiversity, the sharp rise in the cost of food, agricultural inputs and energy, as well as the financial crisis hitting hard on South Africa. He reels off stats with an almost cult-like enthusiasm. “A well looked after Jersey cow that has grown up on pasture should give you 50 lactations. Do you know what the average lactation in South Africa is? Two point one. They are treated as monogastrics and fed a heavy corn diet three times a day. As a result the milk is so high in pus that they are forced to homogenise it. “Of course people are going to be allergic to it.”

I have always wondered why so many people are “allergic to dairy”. South Africa should be the land of milk and honey; instead it is the land of cheap chemicalised food. “We have the highest obesity rate in the world. The rural Africans understood the value of milk, a whole food, but they lost the tradition when they came to the cities to work.” Personally, says Farmer Angus, “I think that consumers have to think about food differently and eat differently. They need to be conscious that behind a kilo of tomatoes lies a lot of work. They need to know where their food comes from and what goes into it. “People are living on more and more processed foods, so the body is craving nutrients. The only thing that the people in agriculture agree on is that the nutrient content of food has been in decline for 120 years. The carrots your grandmother ate and the ones you eat might look the same but on a nutritional level they are entirely different. “Most of us can grow our own vegetables, we can all make our own worm compost which is the best fertiliser of all. South Africa has got a million unemployed people. Why are they not growing their own food? Here’s why. There is a stigma attached to farmers which is why so few guys grow their own food in a place like Khayelitsha. They want to wear zoot suits and drive Beemers.” McIntosh’s new project is producing first grade grass fed, pesticide free food at an affordable price. Last week, wandering the aisles of Checkers, I came across such usually unaffordable products as pancetta, coppa, prosciutto at a price within my budget. Let us give thanks for the pig. Pancetta made from the belly, coppa from the neck and prosciutto from the leg and Black Forest ham to die for from the loin, a real feast. But not a feast for pigs, especially in South Africa. “I only know two farmers who do not cage their pigs,” says McIntosh. The European Parliament’s Agriculture Committee has recently called on the European Commission to propose a revision of the EU directive on farmed animals with the objective of phasing out the use of cages in animal farming. McIntosh’s move to supermarket selling is not only significant because people like me can afford to buy it but it is the first time that grass-fed beef is being sold at the same price as feedlot products. “But more important,” says Farmer Angus, “this is a truly costed item. The beef you buy in a shop is not really costed, the antibiotic resistance is not costed, the inflammatory diseases you get are not costed. There is a whole lot of stuff that is not in the price, so true cost accounting is another thing that has to be on the table in order to keep any ethical enterprise going.” “This stuff has been outdoors reared, it is not imported and most important it has been cured without adding nitrates or nitrites plus the chemical arsenal that fires up most commercial foods. Our charcuterie, made by Gastro Foods, is the only charcuterie in South Africa cured without added nitrates or nitrites. “We have the space, we have the weather, all we need is the absolute desire for better nutrition. “And there are rewards. The carbon in our soil has increased and we get paid credit for that. What people don’t realise is that the vegan diet that everyone is trying to ram down our throats is destructive to the ecology. Whereas this is generative to the ecology. In the vegan utopia there are no animals, so how do they make the food for the plants? They can’t make animal based fertiliser or compost so they have to use chemicals. “Actually, we have no choice. We go the ethical route or we die.” As Joel Saliton, a farmer in the USA famous for his ethical practices, says, “If you think organic food is expensive, try cancer.” A study 2020 conducted by the insurance comparison website Compare The Market, which ranked the healthiest and unhealthiest countries – all part of the Organisation for Economic and Co-operation Development, found that South Africa is the “unhealthiest country in the world”. A separate study, The Indigo Wellness Index, which tracks the health and wellness status of 151 countries, also found South Africans were dangerously unhealthy and ranked SA the unhealthiest country in the world in 2019. Meanwhile, in 2016, the World Health Organisation (WHO) estimated 28.3% of adults in South Africa were obese. This was the highest obesity rate for the sub-Saharan African countries recorded by the WHO. Source: dailymaverick |

Archives

January 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed