|

London’s food-growing schemes offer harvest of fruit, veg and friendship. Behind a row of local authority maisonettes in Islington, north London, on a sun-drenched Tuesday morning, the air hums with insects. Landing bees bend the stems of a patch of lavender as Peter Louis, 60, clears overgrowth with shears.“I come here in winter probably once or twice a week; in summer probably about two or three times a week,” he says. Louis lives alone and is out of work because of poor health. But at the project he can meet friends, and even when he doesn’t the work is a salve to his isolation. “Since the Covid lockdown I suffer from anxiety, stress and depression, and I’m a hands-on person: I have to do something, sitting at home won’t help me,” he says. “And at the end of the day I feel really good. It’s not because I might have fruit or veg to get out of it; it’s the fact that we’re doing this for everyone.” Islington is London’s most crowded borough: 236,000 people crammed into 5.74 sq miles. Land is scarce and expensive: Family homes with gardens change hands for £1m-plus, but almost a third of the borough’s households have no private outdoor space. Space is so tight Islington cannot meet its legal requirement to provide residents with allotments. It is hardly the ideal location for growing food. But for the past 12 years growing food is exactly what the Octopus Community Network has been doing here. The charity runs eight growing sites, located in areas of serious deprivation, and supports a number of other smaller initiatives. They offer access to nature, education and for socialising. And, when harvest time comes, produce is distributed to the community, providing fresh organic vegetables to families that struggle to afford them. On the Hollins and McCall Estate in Tufnell Park on Tuesday, at Octopus’s community plant nursery, six women are potting up vegetable shoots. The nursery, with a range of beds, a polytunnel, various composters and a shed full of equipment and supplies, is Octopus’s education and learning hub. “The beds are demonstrations of different kinds of growing techniques,” says Frannie Smith, the charity’s full-time community cultivator, overseeing the work. “Then the plants get given away to community groups across Islington to help facilitate their growing. Everything here is about making connections with people that want to be involved with urban food growing in Islington.” AdvertisementDaniel Evans, a researcher at the school of water, energy and the environment at Cranfield University, in Bedfordshire, says growing food in towns and cities can deliver ecosystem benefits, “which are much more than just about putting food on a plate”. Recently Evans worked with colleagues from the universities of Lancaster and Liverpool in scouring every single piece of research they could find on the benefits of farming areas in urban spaces. Vegetation of the right kinds are particularly good for sequestering carbon from the atmosphere, regulating microclimates, harbouring biodiversity, encouraging pollination, and restoring soils, they found. In some circumstances, green spaces can even mitigate natural disasters by, for example, absorbing flood water. “There are benefits also to humans, in what we call cultural services, things like recreation,” he says. People getting out into the allotment or community garden can often bring them not only physiological but mental health benefits as well. Often it allows them to interact with people who they wouldn’t necessarily live or work near, thereby kind of enhancing those societal relations and, for some of them, it’s a great opportunity to get, you know, spiritual experience, a sense of being in a green space, whereas most towns and cities are pretty much grey.” Smith finds a range of ways to get people involved. Members of the local Good Gym help carry deliveries of compost. Residents of a nearby halfway house for recovering addicts till the soil of a church garden alongside wealthy octogenarians. Soon, Octopus will begin a partnership with Mencap to teach disabled adults, as well as volunteers to work with them. But, as many social and psychological benefits as a scheme such as Octopus brings, the food growing can not just be an afterthought. “What we’ve seen in the last few years now is a real need to start thinking about local food growing, or at least sharing out the load,” says Evans. “The UK has a great reliance on food imports. The UK a couple of years ago was importing about 84% to 85% of food; about 46% of vegetables that are consumed in the UK are imported from abroad. “So, of course, when you have a crisis event, like a pandemic or like Brexit, that can really threaten supply. And so if you get local authorities or people growing in their local community together, just helping out producing fruit and vegetables for that local community, then you’re helping to lessen the severity of those shocks.” Eight-and-a-half miles south, across the River Thames, and 33 metres under the streets of Clapham, is an underground farm run by Zero Carbon Farms (ZCF) an entirely different kind of urban food-growing project, which says it uses 70% less water and a fraction of the space of a conventional farm. Evans says the future is probably a mix of the Octopus and ZCF models. “Because there’s quite an interesting paradox here. You get more people into a city, and then you’ve covered up all the soils for those residential buildings and you’ve not got anywhere to grow food any more. So we need to think quite creatively. This is where the hi-tech and digital might come in, about how we use some of these spaces to alleviate that issue.” But a project such as ZCF lacks key elements offered by Octopus, Evans adds. “The real question really here is how does it affect the individual life – you know, the individual urban dweller? “I think cases like the Octopus community – which is not hi-tech, it’s pretty accessible to all, it brings together a wide variety of people from the local neighbourhood – that is, in a sense, what creates sustainability, because we can’t always have experts and specialists doing these things on behalf of everyone,” he says. “We need to get the local community involved so that they in a sense help feed themselves and help sustain their own futures.” … we have a small favour to ask. Tens of millions have placed their trust in the Guardian’s fearless journalism since we started publishing 200 years ago, turning to us in moments of crisis, uncertainty, solidarity and hope. More than 1.5 million supporters, from 180 countries, now power us financially – keeping us open to all, and fiercely independent. Unlike many others, the Guardian has no shareholders and no billionaire owner. Just the determination and passion to deliver high-impact global reporting, always free from commercial or political influence. Reporting like this is vital for democracy, for fairness and to demand better from the powerful. And we provide all this for free, for everyone to read. We do this because we believe in information equality. Greater numbers of people can keep track of the global events shaping our world, understand their impact on people and communities, and become inspired to take meaningful action. Millions can benefit from open access to quality, truthful news, regardless of their ability to pay for it. Source: Guardian A growing body of research suggests a connection between the pesticide paraquat and Parkinson’s disease. Agricultural workers in the United States currently use more than 400 different pesticides on their crops to ensure “higher yields and improved product quality.” These pesticides, however, threaten the health of people who work with them on farms or agricultural land and of those who live near these areas. Two of the most dangerous pesticides that are still in use in the U.S. are paraquat and rotenone. Exposure to these pesticides was found to lead to an increased risk of developing Parkinson’s disease, according to various studies. Paraquat was first commercially produced in 1961 and is used to destroy weeds and grasses resistant to glyphosate, another toxic pesticide sold across the country under the name Roundup. As for rotenone, it was formulated in 1895, but it was only during the last century that it started being employed on a large scale to get rid of unwanted herbs and pests. Paraquat is extremely dangerous and poisonous, and a single sip of this pesticide can immediately cause death. For this reason, it is a “restricted use pesticide,” which means that agricultural workers who intend to use it have to undergo special training before “mixing, loading, and/or applying paraquat.” During this special training, people who work with this pesticide are taught about the toxicity of paraquat, how to apply it safely to crops, and how to minimize exposure while working with it. However, even if paraquat is used correctly, it can still cause significant health risks for agricultural workers. When they take off their protective equipment, vapors of paraquat from the crops can easily travel with them to their farms or homes. And there is also the danger of workers unavoidably inhaling the pesticide. Paraquat can also infiltrate groundwater and soil, causing serious environmental damage. Why Do Authorities Still Allow the Use of Paraquat? Paraquat is applied to more than 100 crops throughout the country. Developing a pesticide as effective as paraquat is hard work. This is one of the reasons why the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) continues to allow the use of paraquat in the United States. Presently, paraquat is banned in more than 50 countries, including China, the United Kingdom, Thailand and the European Union. Nevertheless, it remains one of the most widely used pesticides in developed countries like the United States and Australia. Unsettlingly, more than 8 million pounds of paraquat is used throughout the U.S. every year, according to a 2019 press release by the Center for Biological Diversity, with California ranking first as the state using the most pesticides in the U.S., according to the 2016 data provided by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), which was published by Priceonomics. California made up for more than 11 percent of all pesticides used nationally. The state “[used] nearly twice as much as the second-ranking state, Washington,” according to Priceonomics. Paraquat is still used on crops because it spares agricultural workers “arduous labor,” according to Syngenta, an agricultural company that produces paraquat. The pesticide also “[protects] against invasive weeds and [helps] produce agronomically important crops like soy, corn and cotton.” Given the popularity of the pesticide, paraquat can be found on the market under numerous brand names, including, Blanco, Gramoxone, Devour, Parazone and Helmquat. In 2019, the EPA stated in a draft report on paraquat that there is “insufficient evidence” to link the pesticide to human health concerns. As a result, the agency deemed paraquat safe for use in the United States as a “Restricted Use Product.” In 2019, Representative Nydia Velázquez (D-NY) introduced the Protect Against Paraquat Act, which seeks to prohibit the sale and use of paraquat in the country. There has, unfortunately, been no further substantial progress relating to the bill since then. As of early 2021, the EPA has been considering renewing its approval for paraquat. The agency is expected to make a decision on this issue by the end of 2022. In the meantime, the EPA advises people to take the following precautions until new regulations come into effect:

The Link Between Paraquat Exposure and Parkinson’s Disease Even though the EPA states there is insufficient evidence to support the link between paraquat exposure and Parkinson’s disease, numerous reputable medical studies beg to differ. For instance, according to a Farming and Movement Evaluation (FAME) study, which included 110 people who had developed Parkinson’s disease and 358 matched controls, there is a link between rotenone and paraquat and Parkinson’s disease. “People who used either pesticide developed Parkinson’s disease approximately 2.5 times more often than non-users,” stated a press release by the National Institutes of Health, one of the agencies that was involved with this study. Parkinson’s disease is a disorder affecting the brain “that leads to shaking, stiffness, difficulty with walking, balance, and coordination,” according to the National Institute on Aging. The symptoms “usually begin [appearing] gradually and get worse over time.” Regular exposure to paraquat is known to cause Parkinson’s disease by increasing the risk of developing the disease by a whopping 250 percent, according to a 2018 study by Canada’s University of Guelph. A medical study published in the American Journal of Epidemiology revealed that exposure to paraquat and another pesticide called maneb within 1,600 feet of a home heightened the risk of developing Parkinson’s disease by 75 percent. People heavily exposed to paraquat who are susceptible to developing Parkinson’s disease include agricultural workers, farmers, people working on animal farms, individuals who reside on farms, and people who live in a rural area and drink well water. Additionally, people working as chemical mixers and tank fillers are also at risk of developing Parkinson’s disease due to their contact with paraquat. Drinking well water from a location close to a crop to which paraquat has been applied can be dangerous because the pesticide can easily reach the groundwater. Those frequently exposed to paraquat-contaminated water are at risk for the gradual accumulation of the pesticide in their bodies, posing a health danger. When someone is exposed to paraquat, the pesticide tends to travel through the lungs or the stomach and eventually reaches a portion of the brain medically known as the substantia nigra region. This brain region is responsible for releasing dopamine, a crucial neurochemical that plays a significant role in how many systems of the central nervous system function—from movement control to cognitive executive functions. Once paraquat reaches the substantia nigra region, it depletes the neurons that produce dopamine, a process that is associated with Parkinson’s disease. The damage caused by paraquat to these neurons can ultimately result in the impairment of essential brain functions. The Future Is Organic Because fruits, vegetables and cereals harvested from organic crops have been treated with natural and synthetic pesticides, which are less likely to cause health problems, they are the perfect alternative to conventionally grown produce. Natural and synthetic pesticides are not as toxic as paraquat or glyphosate and include copper hydroxide, horticultural vinegar, corn gluten, neem and vitamin D3. Furthermore, organic products usually have more nutrients, such as antioxidants. People with allergies to foods, chemicals or preservatives can greatly benefit from such healthy food sources. They may even notice that their symptoms alleviate or go away when they eat exclusively organic food. However, the downside of organic food and growing organic crops is that they require more time, energy and financial resources. There is a greater labor input by farmers when it comes to organic crops, which makes these products more expensive. Another reason why organic food is pricier than conventionally grown produce is that organic agricultural farmers do not produce enough quantity of a single product to reduce the overall cost. The regular maintenance of organic crops is also time-consuming, as farmers have to be very careful with unconventional pesticides used to keep weeds, unwanted herbs and pests at bay during organic farming. Even so, eating organic is undoubtedly the future, as most nonorganic produce contains significant traces of toxic pesticides such as paraquat that inevitably accumulate in our bodies over time, being able to trigger severe diseases in the future. While eating organic food may be more expensive, it is wiser to invest in these products given the health benefits. However, it is true that the accessibility and affordability of healthy organic foods is a strong issue among the U.S. food system inequities. Nowadays, organic foods don’t necessarily come from small local farms. They are largely a product of big businesses, most of them being produced by multinational companies and sold in chain stores. These leading food and agriculture companies should invest more in the consumers’ well-being and offer nutritious food affordable to all communities. One solution would be the implementation of government schemes to promote organic farming and incentivize farmers to transition to organic agriculture. Instead of supporting factory farms, the government could support sustainable family farms, which often farm more ethically. It could lower healthy food costs and address the health crisis brought on by the mass consumption of unhealthy processed foods. Organic foods will not only lead to better health but will also discourage the practice of applying hazardous pesticides on conventionally grown crops, doing away with the health and environmental hazards involved in the process. Source: https://independentmediainstitute.org/efl-tat-20220215/

Patrick Frankel on a landscape where carrot price is the same as a vanilla shot in coffee Nestled in thick forests around Doneraile in north Cork, organic farmer Patrick Frankel has made a living for himself and his family from six acres of a market garden and four polytunnels. The focus on quality has worked, but Frankel is as concerned as every other vegetable grower in the State about the public and the supermarkets’ demand for lower prices, and the need to keep growers in business. “In a market where a normal bag of carrots will cost the same as a 50-cent shot of vanilla for a coffee, it should be easy to see how most vegetable growers are frustrated,” he said. Before Covid-19 struck two years ago, Frankel was supplying up to 30 restaurants with fresh vegetables. Hit by closures, he moved online with Neighbourfood, selling directly to customers. “When the lockdown started, we fell off a cliff with our restaurant customers but two weeks later we were up selling again thanks to Neighbourfood contacting us,” he said. “We sell mainly salad and charge €3 for a 125g bag. Consumers like that it’s chemical free. From operating our own market stall, I know it’s not just the middle class who care about buying local, organic food. “But I don’t know how to convey to consumers the time, effort and skill that’s needed in vegetable production. There’s a generational disconnect there.” Frankel has been in business for 16 years. He has had a few complaints that some of Doneraile farm’s vegetables “weren’t symmetrical, which is just harder to do in a small organic system”. Price vs qualityThe Irish eat a lot of fruit and vegetables, better than elsewhere in the European Union, while consumption jumped by a quarter during the pandemic’s home cooking “craze”, where more than €600 million was spent. However, the biggest driver is price, not quality. Nearly half of people say prices dictate whether a bag of vegetables is bought or not – all of which keeps the State’s 200 growers – and especially the 135 larger ones on tight margins. A one cent change is often the difference between profit and loss, say some growers. One, who did not want to be named, told of how he was “laughed out of the room” recently when he asked one supermarket for an increase. “Electricity, labour and fertiliser costs have all gone up. Last year, we would have paid around €190,000 for fertiliser and we’re expecting to have to pay €400,000 for the same amount this year,” he said. He has warned he will go out of business if prices do not rise: “Part of it is they want to see if they can bring in the same vegetables cheaper from Scotland or Holland.” Relations with buyers are poor: “A lot of them would cut you as soon as look at you and it’s all a bit sinister and horrible to be honest. I genuinely believe that there will be shortages on the shelves this year. “I don’t know where the retailers are thinking they can get Irish vegetables in the future if they’re driving growers out like this.” He said pledges by Minister for Agriculture Charlie McConalogue have done little to help. Imports already feature heavily. Over 60,000 tonnes of apples and 47,000 tonnes of onions are imported annually, while 72,000 tonnes of foreign-grown potatoes are bought, too. Despite talk of inflation, prices have fallen since 2013. However, the supermarkets defend themselves. Aldi Ireland’s group buying director John Curtin insists they have built “long-term, mutually beneficial relationships with our suppliers. Retailers drive organic growers out of businessCost pressures“Aldi is a committed supporter of both Irish growers and Irish food and drink producers, paying fair prices to all its Irish suppliers,” he said, adding that it is working with suppliers faced with significant cost pressures. The company’s focus on sourcing in-season Irish produce remained, he said: “We spent over €1 billion with Irish producers last year, an increase of almost 20 per cent on 2020, including €250 million on Irish food and drink [at Christmas].” Lidl was recently criticised by farmers for slashing the price of its organic range, but the company insists that the items listed in its weekly super saver deal “in no way impacts the price paid to suppliers”. Faced with pressures, more farmers want to go organic. Eleven growers, backed by the Irish Organic Association’s use of a European Union fund, saw sales rise from €3.8 million to €8.1 million over three years. However, bread tomorrow is not bread today, with growers complaining that supermarkets boast of paying their own employees the living wage, but leaving vegetable suppliers on the minimum wage. “I invested half a million euro into my business 10 years ago but if I had the same choice again today, I wouldn’t do it,” said one grower, who cannot be named to protect his relationship with his supplier. Back in Doneraile, Patrick Frankel knows there is a battle to convince a doubting public. Yes, he must cut costs, he says, but he must also teach people to grow their own vegetables. If only so they learn how hard it is to grow quality food. Source: Irish Times

Olive tree growing deals with a tree of great historical, economic and environmental importance, which is why it is deeply rooted in the traditional habits of every producer. The organic cultivation of olive tree is based on methods of rejuvenation of the olive tree grove soil, the recycling of by-products and other available organic materials and the reproduction and protection of the natural environment. It is the method of olive production that aims to produce an excellent quality olive oil (meaning extra virgin olive oil), free from pesticide residues, which undermine health, and reduces contamination of soil, water and air. It also contributes to the preservation of the diversity of valuable plants of the area, wild animals and genetic material of the olive tree. Creation of an organic olive tree grove Suitable location: Before creating or setting up a new organic olive tree grove, it is necessary to study and take into account the soil-climatic conditions of the area. Locations with limited sunshine, long periods of shading and frost-affected areas should be avoided as much as possible. Coastal areas and areas with cool weather and high relative humidity, especially during the summer and autumn months, should not be preferred, because such areas favour high infestations from Olive fruit fly (Thakos (Δάκος) in Greek). It is also very important the principle that the location where the organic crop will be planted should not be affected or neighboured by conventional olive groves. In a sloping location protection measures must be taken against the transfer of rainwater from conventional olive groves or other conventional crops. Also, if possible, the plantation should be isolated with a tall natural windbreaker, so that it is not affected by spraying that will be carried out in conventional olive groves or other crops. Selection of soils and measures for their correction The main concern of every olive tree grower is from the beginning of the conversion or planting of the organic olive grove to do all those actions to significantly improve the physical and chemical properties of the soil for normal nutrition and growth of trees. We must keep in mind that the soil is a living organism with a number of important biological processes that in turn can feed the olive trees. Heavily used and damaged soils, with a limited concentration of organic matter, do not help the olive trees to grow and perform satisfactorily. Boring and cohesive soils that retain enough moisture cause rotting in olive trees and reduce or inhibit the prevention of various nutrients. Soils poor in organic matter are corrected, either by adding organic matter or animal manure or by applying green fertilizer, which is done by incorporating in the soil a mixture of legumes (vetch, broad beans, peas, etc.) with grass plants, with the aim of increasing organic matter and nitrogen. Green manure is the cheapest method due to the advantages it provides both to the ecological system (non-dependence on the imported expensive system of organic matter), but also in terms of cultivation (competition with some weeds, etc.). Also, the addition of organic matter to the soil improves its structure, makes it easier to cultivate the soil from agricultural machinery and allows better absorption and retention of moisture. Olive grove installation and varieties The olive trees of the organic olive grove must be planted at regular distances. Dense planting does not help their normal ventilation. In sparse planting, the entire area of the land is not economically exploited. Olive trees are preferred to have a trunk of normal height to facilitate the necessary cultivation care and normal ventilation. The most suitable varieties for organic farming are considered to be those that are resistant to pests and diseases and are adapted to the soil-climatic conditions of each region. Varieties grafted on wild olives show resistance to soil diseases and develop a large root system. The olive varieties 'Koroneiki', 'Ladoelia' and secondarily 'Picual' show considerable resistance to enemies and diseases. Cultivation care Nutritional requirements of olive trees: Significant amounts of the main nutrients of nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium are removed from the olive grove every year due to the needs of the plant for vegetative growth and production. It is natural that when the quantities removed are greater than those available there will be a reduction in production unless these elements are supplemented. The amount of elements to be added to the soil of each olive grove depends on the type of soil, the available stocks, the cultivation practice followed (pruning, irrigation, etc.) and the production of the year. Consequently, it is not possible for anyone to come up with an ideal fertilisation strategy that applies to all conditions, but it can single out some general guidelines. The most important parameter is always the nutritional requirements of the crop, in this case the olive. The first concern is to replenish at least the nutrients removed by harvesting and pruning. It has been found that on average 100 kg of olives remove from the soil: 0.9 kg Nitrogen (N), 0.2 kg Phosphorus (P), 1.0 kg Potassium (K) and 0.4 kg Calcium (Ca). An amount of nutrients that are trapped in the soil, in non-digestible form (mainly in Phosphorus and Potassium) or even lost by rinsing to the lower layers of the soil, mainly in Nitrogen, must be taken into account. Fertilization methods The fertilization of the organic olive grove aims at the improvement of the soil productivity and the strategy that ensures long-term improvement of the texture and structure of the soil along with the increase of its fertility. Olive fertilization should be based on a program to maintain and rejuvenate the soil of the olive groves. This program is mainly based on the application of the method of green fertilization with legumes, grasses or mixtures, the addition of compost from organic materials, as well as the addition of animal manure, which necessarily comes from animals primarily organic or even extensive breeding. Organic fertilization: An economical and practical way of fertilizing the organic olive grove is the preparation of compote using the plant residues of the olive grove with manure from organically or extensively farmed animals. One way to make organic compote is to use olive leaves from olive mills along with about 10-20% of sheep and goat manure. The construction of this type of organic compote costs money, so it is usually used in the first 3-4 years of conversion of the olive grove into organic. In the following years, olive leaves and other plant residues can be used together with 20-40% oil extracts from the tanks of the oil mills. It is well known that mill waste has a good content of various nutrients, organic matter and microorganisms. The best time to place the compote is immediately after harvest. For every tenth, an average of 2 cubic meters of compost is recommended. The fertilization is supplemented with the integration of the natural vegetation of the olive grove, with the integration of the leaves and branches up to 5 cm thick that are crushed by the cultivation, with the use of special mechanical tools-crushers, as well as with the use of the effluents of the olive mills. Part of this article can be found on gargalianoionline.gr (News from Messinia on time) Freshfel Europe asks for more time and flexibility for new French plastic packaging legislation. On 1 January 2022, a new legislation banning plastic packaging came into force in France. The new law No. 2020-105 of 10 February 2020, also known as “AGEC law", is adopting in the French national law the European Directive (EU) 2019/904 on the reduction of the impact of certain plastic products on the environment into the French national legal framework. The French law is going well beyond the requirements of the European Directive, providing limited flexibility to reach the reduction of plastic products. It only considers a phase-out option for consumers packaging of less than 1,5 kg. Freshfel Europe is urging the European Commission to request France to allow more time for the fresh produce sector to adapt to the new French legislative requirements. Freshfel Europe warned that the new legislation might also significantly endanger other environmental priorities undertaken by the sector, namely its commitments towards food quality and the highest safety ambition for fresh produce as well as waste prevention initiatives. Freshfel Europe also voices its concerns that, pending the introduction of new innovative solutions on stickers, information to consumers might also be compromised. Over the past months, Freshfel Europe and its members extensively discussed the many changes resulting from the new European packaging requirements which reduce the use of plastic and follow the transposition into national law of the European Directive (EU) 2019/904. The fruit and vegetable sector is committed to adhering to European and national environmental and climatic strategies reflected in the European Green Deal and the Farm to Fork Strategy. The fresh fruit and vegetable sector also fully shares the objectives of reducing plastic packaging. This is already widely demonstrated by proactive sectorial initiatives and new business practices to engage in a progressive move out of plastic packaging and search for innovative solutions anticipating legislative requirements. Freshfel Europe laments that the transposition of the European Directive 2019/904 in France has disregarded these efforts and the concerns of public stakeholders, including the European Commission, other Member States, as well as the voices of the private sector both in France and at European level, on the far-reaching implications of the new French law. While some temporary derogations are set by the French decree 2020-105, Freshfel Europe has multiple apprehensions about the fast-tracked introduction of a national legislation that goes well beyond the requirements of the European Directive. This is endangering the good and fair functioning of the Single Market as it opens the door to a proliferation of different rules and timing among its Member States. As of the 1st of January, almost all plastic packagings for sales to consumers as well as all non-home-compostable stickers will be banned in France. This is expected to lead to distortions of competition and discrimination among operators across the European Union. Philippe Binard, General Delegate of Freshfel Europe commented: “While the deadline for plastic phase-out isset in France for 2040, the phase-out target for fruit and vegetables is set on 1st January 2022 with only limited temporary derogations to 2026 for some particularly fragile products. The same pressure is not placed on other food products, hence representing a discriminatory status for the fresh fruit and vegetables,” he added. “The French law is not considering alternative solutions such as the use of recyclable plastic packagings, the ban being the only option. The removal of most of fruit and vegetables plastic packagings with such a short notice is not allowing an alternative to be timely tested and introduced and stocks of existing packaging to be cleared.” Philippe Binard also warned: “The impact of the entry into force of AGEC Law is just as worrying for the adhesive labels affixed to fresh fruit and vegetables sold to French consumers. The major difficulty today is that there is still no company capable of supplying "Agec-compatible" labels being domestic friendly compostable or made of biosource material. The ban on non-home compostable stickers without having an alternative on the market is problematic as it will significantly endanger the labelling of essential information conveyed to consumers on the stickers such as origin, brands, geographical indications, or organic”. First alternatives might only start to be placed on the market at the earliest only towards the end of 2022 at best. While this announcement is to be welcomed, Freshfel Europe considers that it might lead the sector to new costly machinery investment costs. More time should be given to secure for the sector access to a diversity of solutions at affordable conditions before enforcing the new law. Philippe Binard added: “The provisions for stickers in France are very confusing. French producers and traders would be allowed to affix stickers on the fresh produce in France but only if shipped for consumption to another members states or internationally. Affixing labels by operators located outside France would be restricted if the final destination would be France, which is not easy to anticipate for producers at the time of packing.” Freshfel Europe views the French provision on stickers leading to a lot of incoherent consequences and many uncertainties for the free movement of goods within the European Union. Pending the elaboration of alternative solutions for both consumers packaging and stickers, the sector fears as well several side effects of the new rules that should not be overlooked as being also very relevant for the Farm to Fork Strategy. The quality and safety of products might be challenged as well as the food waste sector’s prevention initiatives. The reshape of packaging policies is also expected to further exacerbate the costs increase of packagings for the sector in search of alternative solutions or materials. Given the lack of transparency in the interpretation of the law, the limited flexibility, and the tight deadline for the coming into force of the French Law as from 1 January 2022, Freshfel Europe urged the European Commission to act. On 17 December 2021, in a letter addressed to 6 European Commissioners, Freshfel Europe requested the European Commission to enter into dialogue with the French Authorities to secure more time for the fresh produce sector to adjust to the national French Law until technical solutions for both sales packaging containers and stickers are available. Philippe Binard stated: “It is crucial to allow more time to avoid market disturbances and steps that would deeply endanger the free circulation of goods in the internal market and would generate distortion of competition and discrimination among operators.” He underlined: “The Commission should take all the necessary steps to prevent the proliferation of different rules for the transposition of this directive as it will only lead then to a complex, costly and confusing business environment.” Beyond the individual objective of the plastic strategy, Freshfel Europe insists that it is of paramount importance to protect the competitiveness of the fruit and vegetable sector and prevent the introduction of costly new burdens upon a sector that represent products identified by many as an undisputed essential partner for the solutions to climate, societal, and environmental challenges. https://www.freshplaza.com/article/9385332/freshfel-europe-asks-for-more-time-and-flexibility-for-new-french-plastic-packaging-legislation/

Consumers and corporations are talking the talk about sustainable practices, but independent natural retailers established those roots long ago As sustainable business practices become more and more important to consumers, and as big corporations proclaim their commitment to sustainability, independent natural retailers point out that they've been leading in this area all along. Their tendency to focus on organic products, local sourcing and minimizing waste has been core to their business strategies for decades, and they have often built customer followings based on those principles. "We have held these values near and dear for 29 years," said Steven Rosenberg, founder and chief eating officer, Liberty Heights Fresh in Salt Lake City. "This isn't anything new to us. We feel we should all do our best to use less of the Earth's resources, whether it be water, clean air, healthy soil, less electricity, and certainly less carbon-emitting energy." Likewise, Eli Lesser-Goldsmith, CEO of Healthy Living Market & Café in South Burlington, Vt., said his company prides itself on its nearly four decades of environmentally conscious positioning. "The heart of our business is community sustainability," he says. "It's local grocery shopping; it's all the things that are now being talked about as things humans need to do to be better stewards of the Earth. We are proud that we have actual heritage in the space and actual authenticity." Consumers appear to have their own definitions of what sustainability means, however. Environmental concerns often overlap with interest in societal issues such as fair pay, as well as with consumers' desire to eat more healthfully. Consumers expect that retailers are vetting their suppliers to make sure they are being grown or made under fair working conditions, Rosenberg said. "I feel like a lot of people are connecting the dots," he said. "People want to buy good food, and they want to know that it is going to make them smile as much inside as outside, and the ingredients are going to be things their great-grandmothers would recognize." Lesser-Goldsmith pointed out that not only do consumers all view sustainability differently, each of the brands that supply his stores also have their sustainability story, as does his own store brand. "As the topic of sustainability and climate change evolves, people are forming their own opinions and trying to do what what's best for their community, for the environment, for their wallets and their health," he said. Some companies may be clouding the waters with sustainability claims that lack merit, which makes it difficult for those who are truly making an effort to be sustainable to get their messages across, he added. Mylese Tucker, owner of Nature's Cupboard in Michigan City and Chesterton, Ind., said her stores' customers often use social media to amplify messages around sustainability and supporting local growers, makers and retailers. "We have customers posting all the time on Facebook, talking about how we use local farmers," she said. "Customers are helping us get that message out there, and letting the community know why they should be shopping here." Several customers feel so strongly about sustainability that they even collect the retailer's recycling and its compostable nonfoods waste. "A lot of our customers are really committed, especially those moms who want a better world for their kids," Tucker said. Nature's Cupboard itself is dedicated to doing as much as it can to operate sustainably, using compostable containers in its juice bar and deli, for example. It eliminated plastic bags several years ago, Tucker said. At Liberty Heights Fresh, which has been recognized multiple times for its sustainable practices, Rosenberg said one of the first things he did when he opened the store in 1993 was convert the refrigeration to be more energy-efficient. It also has three gardens within walking distance of the store where it grows thousands of pounds of crops each year. "We want to lead with integrity with everything we do," he said. "If you are going to talk the talk, you had better walk the walk." Source: Supermarket News

Most of us think of gardens as sunny places, which is likely due to the fact that the crops we're used to growing and eating require full sun to thrive. And it's true: those summer veggie gardens brimming with squash, green beans, and tomatoes require a lot of sunlight. Many edible plants, on the other hand, can grow in the shade.For those of us who want to grow more of what we eat, it's critical to understand what we can grow in less-than-sunny conditions. A variety of fruits and vegetables, it turns out, prefers shade, or at least dappled shade, to do their thing. If being experimental and adventurous, with a dash of self-sufficiency, sounds like a good time, the list of shade-tolerant produce below might be just what you're looking for. 1. Ostrich Fern: Every spring, the forest floor is littered with new plant sprouts that have been waiting for some warmth. Ostrich ferns produce an abundance of edible fiddleheads (unfurled fronds) that are similar to asparagus for those in the know. They prefer partially shady locations and grow into lovely ornamental plants for the rest of the year. 2. Ramps: Ramps, also known as wild garlic, grow naturally in deciduous forests where the soil is rich in organic matter. They are spring ephemerals that prefer to bask in the sun before the trees' leaves have returned. Ramps take a while to get going (a few years before harvest), but they are perennials that can produce tasty greens for many years. 3. Creeping Raspberry: Creeping raspberry (thimbleberry) grows low and prolifically in shady areas, such as the understory of food forests, and makes an excellent edible. It produces delicate fruits that are too soft for market transportation. Nonetheless, they have a flavor similar to raspberries and make delicious jams. They prefer full shade. Another advantage is that they are thornless. 4. Wintergreen: Wintergreen is a low-growing evergreen that makes a lovely groundcover and has edible berries and tea-making leaves. Wintergreen's flavor is derived from both the berries and the leaves, as the name implies. This is an excellent groundcover for shady gardens. They can tolerate some sunlight but prefer to be in the shade. 5. Sweet Cecily: Sweet Cecily, a self-seeding member of the carrot family, will quickly spread wherever it is planted. It thrives in partial shade and produces a delicious variety of snacks, as well as attracting a large number of pollinators. Sweet Cecily, like many other wildflowers, prefers to be planted in the fall and will bloom the following spring. Grow 7 food plants in shaded areas6. Arctic Beauty Kiwi When we can grow something vertically, even in shady areas, we save valuable growing space. Arctic Beauty Kiwi thrives in partial shade. It grows to be about 10-12 feet tall and produces divine fruit that resembles hardy kiwis (smooth and green on the outside) rather than the fuzzy kiwis found in supermarkets. 7. Elderberry: Elderberry trees are voracious, quick-growing plants that thrive in wet soil and partial shade. Both the berries and the flowers are medicinal and edible. In general, the berries are used to make jam, syrup, and wine. Teas can be made from flowers. If the trees become too large, they can be pruned and will recover to continue producing. Grow a lot of food in areas that most gardeners believe are off-limits to plants. That is not the case at all. Lots of tasty foods will grow in places where the sun rarely shines.

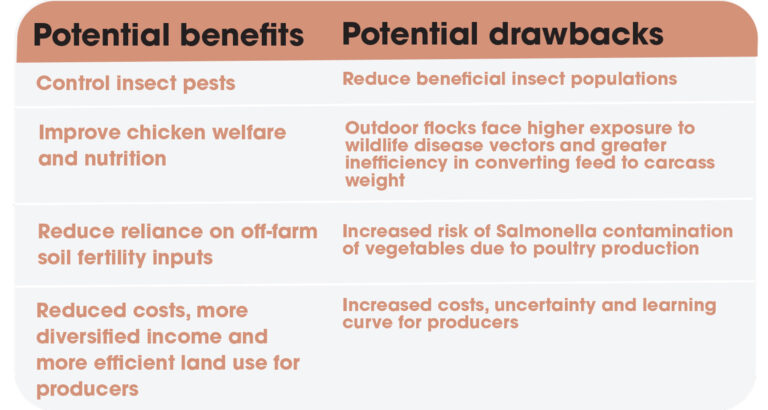

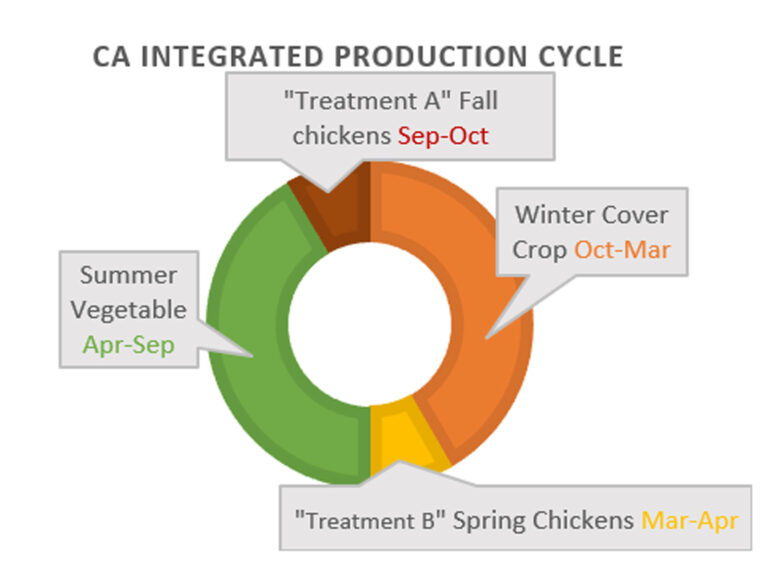

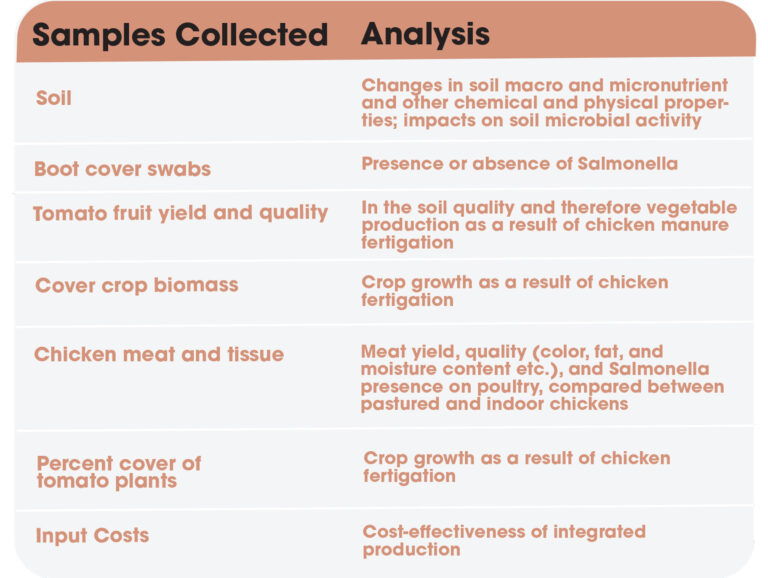

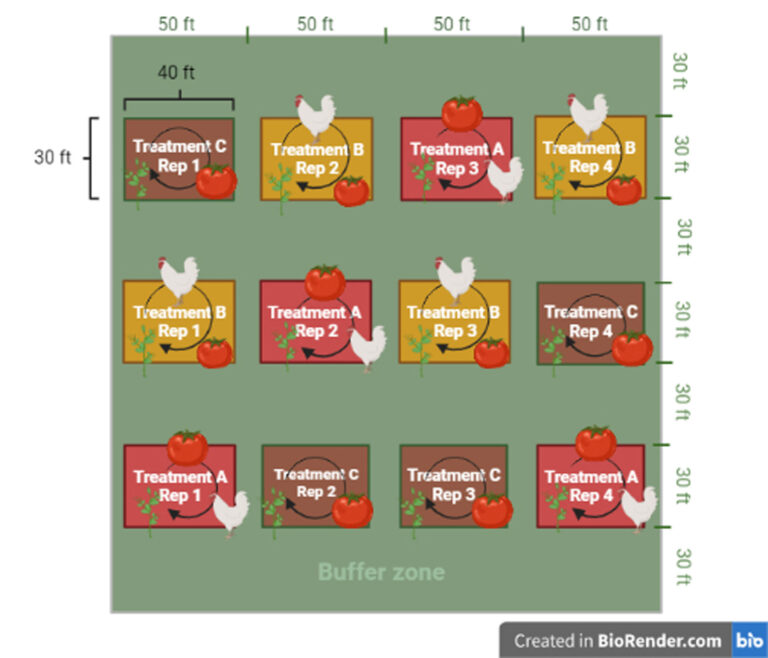

Integrating Chicken and Vegetable Production in Organic Farming Chicken and tomatoes are a tasty duo beloved by many in popular dishes like chicken tikka masala and chicken cacciatore. This combination, delightful in the culinary sense, is also the subject of a recent integrated farming experiment. This fall, researchers at UC Davis harvested the first crop of tomatoes from a 1-acre experimental field and successfully processed the second flock of 130 broiler chickens. This acre is part of a tri-state experiment also taking place at University of Kentucky and Iowa State University, where the experiment was originally spearheaded by horticulture professor Ajay Nair. Funded by USDA, this research aims to produce science-based learnings and best practices for organic agricultural systems that integrate rotational production of crop and poultry together on the same land. Potential of Integrated Production While the idea of chickens alongside crops evokes an image of “traditional farming”, these systems are relatively rare in North America today. Integrated farms have the potential to help organic farmers create a more resource-efficient “closed-loop” system. For vegetable farmers looking to start an integrated system, chickens require the lowest startup costs as compared with other livestock. This type of diversified production may be especially promising given the growing consumer demand for more sustainably and humanely produced chicken. However, there are many beliefs that remain unconfirmed and questions that remain unanswered by scientific research when it comes to integrating poultry production into vegetable cropping. For instance, at what extent does manure deposited by poultry on the farm reduce the need for off-farm soil fertility inputs? What benefits can we observe when crop residue is used to supplement the diets of the chickens? What stocking rate is the most advantageous in these systems? What types of crops and breeds of chicken work the best with poultry production in different regions? And is it feasible to squeeze in a successful yield of broiler production into the transition window between different crop seasons? Finally, can all this be done effectively from a food safety perspective and economically from both a farmer and consumer level? Study Design To better understand and evaluate the potential to integrate poultry with crop farming from multiple perspectives, the research objectives focused on evaluating growth yields, quality of agricultural outputs, food safety risks, agroecological impacts on soil and pests, and economic feasibility of such systems. In this experiment, broilers were raised on pasture starting at around 4 weeks of age to graze on crop residue. In the California iteration of this experiment, we raised two flocks per year in between rotations of vegetable crops in the summer and cover crops in the winter (Figure 1a). Rather than remaining in a fixed location, the pastured broilers are stocked in mobile chicken coops, commonly referred to as “chicken tractors”, which are moved to a fresh plot of land every day for rotational grazing. Four subplots distributed across the field are grazed by chickens before vegetables are planted in the spring (treatment B), and four different subplots are grazed by chickens after vegetable harvest (treatment A). The impacts of grazing on soil and crop production of the two treatments are compared to a third control treatment of only cover crops and vegetables (treatment C), while the impacts of rotational grazing on meat production are compared to an indoor control flock. Collaborating researchers in Iowa and Kentucky are also collecting weed and insect diversity data to better understand the impacts on crop pests and better understand how poultry affect the integrated farmland. Additional studies on animal welfare for the chickens as well as conducting cultivar trials on the success of varieties of different vegetables like lettuce, Brussels sprouts, butternut squash and spinach tested in combination with poultry are being conducted. Challenges Identified and Lessons Learned As the study is still underway, we cannot make any conclusions without testing and re-testing experimental results to confirm their repeatability and statistical significance across more than one growing season. So far, however, we’ve collected a great deal of initial learnings on our integrated systems. Soil Fertility Organic farmers know that soil amendments, such as chicken manure, release nitrogen slowly to crops over time. Factors related to timing of application, precipitation and temperature affect how soil microbes process organic material to ultimately impact the soil quality. In California, although our tomato crop received sufficient subsurface drip irrigation, we suffered low yield and tomato end rot across the treatments. This was due to the fact that our experimental plot was previously conventionally managed and very nutrient depleted, an issue which we attempted to manage by applying organic compost and liquid fertilizer to the entire field to supplement the manure deposited by the chickens. In addition, severe drought during and after the period of manure deposition may have hindered soil microbial activity and, in turn, retarded the decomposition of our cover crop residue and chicken manure into the soil. Meat Production Additional data remains to be collected on subsequent flocks and statistical analysis on the findings have yet to be conducted before conclusions can be drawn. Preliminary results from meat quality analysis indicate that the pasture-raised chicken yielded less drumstick meat than the indoor control and breast meat was darker and less yellow in color. They also yielded redder thigh meat and less moist breast meat than the indoor chicken when cooked. So far, broilers in California that grazed on cover crops in the spring reached a higher average market weight relative to indoor control, while broilers grazed on tomato crop residue in the fall reached a lower average market weight relative to the indoor control. Food Safety No presence of Salmonella has been detected thus far in the soil nor on the poultry produced in the California experiment. Collaborators in Iowa and Kentucky report that persistence of Salmonella associated with the poultry producing soil has not been observed to persist into the harvest period. While these results are promising, it should be noted that Salmonella are relatively common in poultry. Ideally, best practices can be identified that reduce the risk of Salmonella persisting in the soil environment while crops are grown following chicken grazing. Many other anecdotal findings have emerged: In Iowa, a farmer collaborating with researchers to conduct their own on-farm iteration of the experiment has noted positive results from the poultry treatment on their spinach crop; our collaborating researchers also report that the chickens may appear to be eating an insect that is beneficial in their agricultural system, a finding which, if validated, may debunk the perception that their presence on the farm is always advantageous to pest control. In California, we are realizing the impact the design of the chicken tractors has on labor demands. Our 5 x 10 ft-wide wheeled coop was more difficult to move in a tomato production system with raised beds and loose soil as compared to a relatively more even and firm ground in a pasture. It seems apparent that engineering considerations such as wheel type, coop material and coop weight will influence the adaptability of poultry and crop integrations. Careful timing and planning is yet another labor consideration when it comes to transitioning successfully between cropping and poultry husbandry that we encountered. Eagerly, we await to gather more information in the next year until additional conclusions to our research questions can be drawn after the study concludes in 2022.

Additional Resources Nair, A. & Bilenky, M., (2019) “Integrating Vegetable and Poultry Production for Sustainable Organic Cropping Systems”, Iowa State University Research and Demonstration Farms Progress Reports 2018(1). Source: Organic Farmer Magazine This article mentions the difference between certified organic food and conventional food. It is important to mention that the organic food mentioned on www.soilandsun.co.uk is a certified organic food. Organic certification involves application of strict standards and an annual audit from an indepedent auditing on the application of these standards. Failing to follow these standards, farmer or grower are not allowed to trade their product as organic in other words they lose their organic certification status which proves that the product made by them is not anymore organic. A. Organic food are Heathy Organic foods are free from:

Organic foods have different appearances This difference mainly apply to fruits and vegetables. As a consumer you will see fruits with smaller size, cracks or blemishes on the surface. They do not look super shiny and do not have perfect shape but they look imperfect and real. Organic farming is environment friendly and sustainable Due to absence of these toxic pesticides, heavy metals, GMO, herbicides, the organic farming practically conserves the quality of the soil and water. There are reports mentioning that there is a huge contamination of the rivers in Europe with pesticides and they had been used several years before their detection and remain there. The environmental pollution made by pesticides, heavy metals and GMO is non reversible. Organic farming practices are sustainable, as the farmers/growers will not push nature with all its elements animals and trees/plants to produce more especially when there is a bad harvest season. Animal manure or compost are used to feed the soil and weeds are managed by rotating crops. Natural on the food label does not mean organic Many processor use various words such as Natural or Sustainable on the food label to make the consumers think that their products are organic. These foods are not certified organic foods and are full of ingredients from conventional farming which uses all these toxic chemicals starting pesticides i.e round -up to GMO and insecticides and heavy metals. We have an obligation to inform all the consumers about the huge benefits of organic foods to our health and our planet air, soil and water. Sources:

1. Human health implications of organic food and organic agriculture: a comprehensive review Environmental Health volume 16, Article number: 111 (2017) 2. Livestock antibiotics and rising temperatures disrupt soil microbial communities, Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies 3. Food Preservatives and their harmful effects, Dr Sanjay Sharma, International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications, Volume 5, Issue 4, April 2015 4. Effects of Preservatives and Emulsifiers on the Gut Microbiome By: Angel Kaufman Spring 2021 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a baccalaureate degree in Biology in cursu honorum Reviewed and approved by Dr. Jill Callahan Professor, Biology 5. Pesticides and antibiotics polluting streams across Europe, by Damian Carrington, found on https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2019/apr/08 It is an relatively old articles but the damage to the environment remains there. Pesticides and antibiotics are polluting streams across Europe, a study has found. Scientists say the contamination is dangerous for wildlife and may increase the development of drug-resistant microbes. More than 100 pesticides and 21 drugs were detected in the 29 waterways analysed in 10 European nations, including the UK. A quarter of the chemicals identified are banned, while half of the streams analysed had at least one pesticide above permitted levels. The researchers said the high number of pesticides and drugs they found meant complex mixtures were present, the impact of which was unknown. Pesticides are acknowledged as one factor in plummeting populations of many insects and the birds that rely on them for food. Insecticides were revealed to be polluting English rivers in 2017. “The importance of our new work is demonstrating the prevalence of biologically active chemicals in waterways all over Europe,” said Paul Johnston, at the Greenpeace research laboratories at the University of Exeter. “There is the potential for ecosystemic effects.” The research, published in the journal Science of the Total Environment, found herbicides, fungicides and insecticides, as well as antimicrobial drugs used in livestock. The risk to people of antimicrobial drug resistance is well known, but Johnston highlighted resistance to fungicides too. “There are some pretty nasty fungal infections that are taking off in hospitals,” he said. One of the world’s biggest pesticide makers, Syngenta, announced a “major shift in global strategy” on Monday, to take on board society’s concerns and reduce residues in the environment. “There is an undeniable demand for a shift in our industry,” said Alexandra Brand, the chief sustainability officer of Syngenta. “We will put our innovation more strongly in the service of helping farms become resilient to changing climates and better able to adapt to consumer requirements, including reducing carbon emissions and reversing soil erosion and biodiversity decline.” Another major pesticide manufacturer, Bayer, said on Monday it was making public all 107 studies submitted to European regulators on the safety of its controversial herbicide glyphosate. “Transparency is a catalyst for trust, so more transparency is a good thing for consumers, policymakers and businesses,” said Liam Condon, the president of Bayer Crop Science. In March, a federal jury in the US found that the herbicide, known as Roundup, was a substantial factor in causing the cancer of a California man. Pesticides and antibiotics polluting rives in EuropeThe testing techniques used in the new research meant only a subset of pesticides could be detected. Two very common pesticides – glyphosate and chlorothalonil – were not included in the study, meaning the findings represent a minimum level of contamination. The research focused on streams, as these harbour a large proportion of aquatic wildlife. The detection of many pesticides that have long been banned was not necessarily due to continued illegal use, the scientists said, but could be the result of leaching of persistent chemicals that linger in soils. The study took place before the most widely used insecticides were banned by the EU for all outdoor uses. Irish Water said on Monday that EU pesticide levels were being breached in public water supplies across Ireland. In Switzerland, another new study found that soils in 93% of organic farms were contaminated with insecticides, as were 80% of the areas farmers set aside for wildlife. Research revealed in 2013 that insecticides were devastating dragonflies, snails and other water-based species in the Netherlands. The pollution was so severe in places that the ditchwater itself could have been used as a pesticide. A study in France in 2017 found that virtually all farms could slash their pesticide use while still producing as much food. Johnston said: “Farmers don’t want to pollute rivers, and water companies don’t want to have to remove all that pollution, so we have to work to reduce reliance on pesticides and veterinary drugs through more sustainable agriculture. This is not a case of us versus farmers or water companies.” Source: The Guardian

|

Archives

January 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed