|

In the face of intensifying weather patterns like the series of storms pounding the West, regenerative organic farms are demonstrating that the key to resilience is working with nature. As California experiences a historic succession of winter storms, most of us will see extensive reporting on power outages, flooding, and mudslides. But amidst the destruction, there is a story of resilience and preparedness that will get less attention. A small but growing contingent of farmers is poised to not only rebound from the deluge of water, but to benefit from it. These farmers have a valuable lesson to share: ecologically-minded, regenerative organic agriculture that prioritizes soil health is critical to our future. In a region parched by megadrought and greatly affected by human alteration, the landscape cannot absorb rapid, uninterrupted rainfall. Agriculture has overworked much of this state—heavy tillage, lack of crop diversity, and agrochemical use have turned living, absorptive soils into easily eroded dirt. We have also redirected rivers and waterways that once transected the landscape and built on top of floodplains. And through clearcutting and the deprivation of healthy fire cycles, we have destroyed our forests’ natural adaptation to heavy precipitation. Despite our desperate need for this water, we have greatly diminished our ability to receive it. This is particularly bad news in a state that produces over two-thirds of the nation’s fruits and nuts and one-third of its vegetables. Though they are suffering from prolonged water scarcity, most of the farms here will see limited direct benefits to their land from the atmospheric rivers hitting the state this season. Many will also suffer crop losses as their fields are flooded and crops in compacted soils drown. And, come summer, they will likely be back to overpumping underground aquifers and overreliance on surface water (as the Sierra snowpack is now melting earlier than it once did). I teach professionals from all backgrounds about regenerative agriculture through experiential education and the farmers I work with are excited about capturing a significant share of this rain on their land. Of course, they would prefer that it come more gently and not all at once, but that is not the reality here. Elizabeth and Paul Kaiser at Singing Frogs Farm in Sonoma County, widely known for their leadership in ecological farming, have seen their lower lying fields flood 11 out of the last 15 winters due to the hydrology of their land. But instead of causing serious damage, their regenerative methods mean that “the water that hits [their] farm goes into the soil and ground below,” says Elizabeth. That’s because their organic no-till practices, regular compost applications, and diverse crop rotations have added a significant amount of organic matter to the soil, causing it to act as a sponge that absorbs water faster and retains it for longer. So, despite the fact that the soil has taken in over 13 inches since December 26th, Elizabeth says they have been able to start planting their spring crops. Paicines Ranch, further south in San Benito County, is another leader in regenerative agriculture. Paicines integrates livestock into their vineyards year-round in imitation of natural ecosystems, cultivates biodiversity, and also avoids tilling. Paicines has experienced “no runoff from our vineyard since we began managing it regeneratively in 2017, despite being situated atop a hill, and I am eager to see how our soils perform with more rain coming,” said Kelly Mulville, the ranch’s vineyard director. “The vineyard soils are now capable of holding all the water this past series of storms has poured on it.” (Disclosure: The owner of Paicines Ranch is a financial supporter of Civil Eats.) Regenerative organic farmers understand that extreme weather patterns are not novel. California’s history is one of drought, flood, and fire that cannot be conquered. Nor should they be; these forces have shaped an abundant landscape, one which has supported human civilization for millennia. But as climate change increases the severity and variability of these forces, adaptation is as important as ever. Ecologically minded farmers are keen observers of nature. Instead of fighting against it, they harness its natural processes to grow food. Instead of simplifying landscapes, they cultivate biodiversity above and belowground, which creates resilience. The healthy soils on these farms are full of life and decaying matter, commonly referred to as soil organic matter. This life creates soil pores (up to 50 percent of total soil volume) and glues particles together, allowing water to infiltrate rapidly without washing it away or drowning plants. Source: Ryan's Peterson article from Civil Eats A growing body of research suggests a connection between the pesticide paraquat and Parkinson’s disease. Agricultural workers in the United States currently use more than 400 different pesticides on their crops to ensure “higher yields and improved product quality.” These pesticides, however, threaten the health of people who work with them on farms or agricultural land and of those who live near these areas. Two of the most dangerous pesticides that are still in use in the U.S. are paraquat and rotenone. Exposure to these pesticides was found to lead to an increased risk of developing Parkinson’s disease, according to various studies. Paraquat was first commercially produced in 1961 and is used to destroy weeds and grasses resistant to glyphosate, another toxic pesticide sold across the country under the name Roundup. As for rotenone, it was formulated in 1895, but it was only during the last century that it started being employed on a large scale to get rid of unwanted herbs and pests. Paraquat is extremely dangerous and poisonous, and a single sip of this pesticide can immediately cause death. For this reason, it is a “restricted use pesticide,” which means that agricultural workers who intend to use it have to undergo special training before “mixing, loading, and/or applying paraquat.” During this special training, people who work with this pesticide are taught about the toxicity of paraquat, how to apply it safely to crops, and how to minimize exposure while working with it. However, even if paraquat is used correctly, it can still cause significant health risks for agricultural workers. When they take off their protective equipment, vapors of paraquat from the crops can easily travel with them to their farms or homes. And there is also the danger of workers unavoidably inhaling the pesticide. Paraquat can also infiltrate groundwater and soil, causing serious environmental damage. Why Do Authorities Still Allow the Use of Paraquat? Paraquat is applied to more than 100 crops throughout the country. Developing a pesticide as effective as paraquat is hard work. This is one of the reasons why the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) continues to allow the use of paraquat in the United States. Presently, paraquat is banned in more than 50 countries, including China, the United Kingdom, Thailand and the European Union. Nevertheless, it remains one of the most widely used pesticides in developed countries like the United States and Australia. Unsettlingly, more than 8 million pounds of paraquat is used throughout the U.S. every year, according to a 2019 press release by the Center for Biological Diversity, with California ranking first as the state using the most pesticides in the U.S., according to the 2016 data provided by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), which was published by Priceonomics. California made up for more than 11 percent of all pesticides used nationally. The state “[used] nearly twice as much as the second-ranking state, Washington,” according to Priceonomics. Paraquat is still used on crops because it spares agricultural workers “arduous labor,” according to Syngenta, an agricultural company that produces paraquat. The pesticide also “[protects] against invasive weeds and [helps] produce agronomically important crops like soy, corn and cotton.” Given the popularity of the pesticide, paraquat can be found on the market under numerous brand names, including, Blanco, Gramoxone, Devour, Parazone and Helmquat. In 2019, the EPA stated in a draft report on paraquat that there is “insufficient evidence” to link the pesticide to human health concerns. As a result, the agency deemed paraquat safe for use in the United States as a “Restricted Use Product.” In 2019, Representative Nydia Velázquez (D-NY) introduced the Protect Against Paraquat Act, which seeks to prohibit the sale and use of paraquat in the country. There has, unfortunately, been no further substantial progress relating to the bill since then. As of early 2021, the EPA has been considering renewing its approval for paraquat. The agency is expected to make a decision on this issue by the end of 2022. In the meantime, the EPA advises people to take the following precautions until new regulations come into effect:

The Link Between Paraquat Exposure and Parkinson’s Disease Even though the EPA states there is insufficient evidence to support the link between paraquat exposure and Parkinson’s disease, numerous reputable medical studies beg to differ. For instance, according to a Farming and Movement Evaluation (FAME) study, which included 110 people who had developed Parkinson’s disease and 358 matched controls, there is a link between rotenone and paraquat and Parkinson’s disease. “People who used either pesticide developed Parkinson’s disease approximately 2.5 times more often than non-users,” stated a press release by the National Institutes of Health, one of the agencies that was involved with this study. Parkinson’s disease is a disorder affecting the brain “that leads to shaking, stiffness, difficulty with walking, balance, and coordination,” according to the National Institute on Aging. The symptoms “usually begin [appearing] gradually and get worse over time.” Regular exposure to paraquat is known to cause Parkinson’s disease by increasing the risk of developing the disease by a whopping 250 percent, according to a 2018 study by Canada’s University of Guelph. A medical study published in the American Journal of Epidemiology revealed that exposure to paraquat and another pesticide called maneb within 1,600 feet of a home heightened the risk of developing Parkinson’s disease by 75 percent. People heavily exposed to paraquat who are susceptible to developing Parkinson’s disease include agricultural workers, farmers, people working on animal farms, individuals who reside on farms, and people who live in a rural area and drink well water. Additionally, people working as chemical mixers and tank fillers are also at risk of developing Parkinson’s disease due to their contact with paraquat. Drinking well water from a location close to a crop to which paraquat has been applied can be dangerous because the pesticide can easily reach the groundwater. Those frequently exposed to paraquat-contaminated water are at risk for the gradual accumulation of the pesticide in their bodies, posing a health danger. When someone is exposed to paraquat, the pesticide tends to travel through the lungs or the stomach and eventually reaches a portion of the brain medically known as the substantia nigra region. This brain region is responsible for releasing dopamine, a crucial neurochemical that plays a significant role in how many systems of the central nervous system function—from movement control to cognitive executive functions. Once paraquat reaches the substantia nigra region, it depletes the neurons that produce dopamine, a process that is associated with Parkinson’s disease. The damage caused by paraquat to these neurons can ultimately result in the impairment of essential brain functions. The Future Is Organic Because fruits, vegetables and cereals harvested from organic crops have been treated with natural and synthetic pesticides, which are less likely to cause health problems, they are the perfect alternative to conventionally grown produce. Natural and synthetic pesticides are not as toxic as paraquat or glyphosate and include copper hydroxide, horticultural vinegar, corn gluten, neem and vitamin D3. Furthermore, organic products usually have more nutrients, such as antioxidants. People with allergies to foods, chemicals or preservatives can greatly benefit from such healthy food sources. They may even notice that their symptoms alleviate or go away when they eat exclusively organic food. However, the downside of organic food and growing organic crops is that they require more time, energy and financial resources. There is a greater labor input by farmers when it comes to organic crops, which makes these products more expensive. Another reason why organic food is pricier than conventionally grown produce is that organic agricultural farmers do not produce enough quantity of a single product to reduce the overall cost. The regular maintenance of organic crops is also time-consuming, as farmers have to be very careful with unconventional pesticides used to keep weeds, unwanted herbs and pests at bay during organic farming. Even so, eating organic is undoubtedly the future, as most nonorganic produce contains significant traces of toxic pesticides such as paraquat that inevitably accumulate in our bodies over time, being able to trigger severe diseases in the future. While eating organic food may be more expensive, it is wiser to invest in these products given the health benefits. However, it is true that the accessibility and affordability of healthy organic foods is a strong issue among the U.S. food system inequities. Nowadays, organic foods don’t necessarily come from small local farms. They are largely a product of big businesses, most of them being produced by multinational companies and sold in chain stores. These leading food and agriculture companies should invest more in the consumers’ well-being and offer nutritious food affordable to all communities. One solution would be the implementation of government schemes to promote organic farming and incentivize farmers to transition to organic agriculture. Instead of supporting factory farms, the government could support sustainable family farms, which often farm more ethically. It could lower healthy food costs and address the health crisis brought on by the mass consumption of unhealthy processed foods. Organic foods will not only lead to better health but will also discourage the practice of applying hazardous pesticides on conventionally grown crops, doing away with the health and environmental hazards involved in the process. Source: https://independentmediainstitute.org/efl-tat-20220215/

Patrick Frankel on a landscape where carrot price is the same as a vanilla shot in coffee Nestled in thick forests around Doneraile in north Cork, organic farmer Patrick Frankel has made a living for himself and his family from six acres of a market garden and four polytunnels. The focus on quality has worked, but Frankel is as concerned as every other vegetable grower in the State about the public and the supermarkets’ demand for lower prices, and the need to keep growers in business. “In a market where a normal bag of carrots will cost the same as a 50-cent shot of vanilla for a coffee, it should be easy to see how most vegetable growers are frustrated,” he said. Before Covid-19 struck two years ago, Frankel was supplying up to 30 restaurants with fresh vegetables. Hit by closures, he moved online with Neighbourfood, selling directly to customers. “When the lockdown started, we fell off a cliff with our restaurant customers but two weeks later we were up selling again thanks to Neighbourfood contacting us,” he said. “We sell mainly salad and charge €3 for a 125g bag. Consumers like that it’s chemical free. From operating our own market stall, I know it’s not just the middle class who care about buying local, organic food. “But I don’t know how to convey to consumers the time, effort and skill that’s needed in vegetable production. There’s a generational disconnect there.” Frankel has been in business for 16 years. He has had a few complaints that some of Doneraile farm’s vegetables “weren’t symmetrical, which is just harder to do in a small organic system”. Price vs qualityThe Irish eat a lot of fruit and vegetables, better than elsewhere in the European Union, while consumption jumped by a quarter during the pandemic’s home cooking “craze”, where more than €600 million was spent. However, the biggest driver is price, not quality. Nearly half of people say prices dictate whether a bag of vegetables is bought or not – all of which keeps the State’s 200 growers – and especially the 135 larger ones on tight margins. A one cent change is often the difference between profit and loss, say some growers. One, who did not want to be named, told of how he was “laughed out of the room” recently when he asked one supermarket for an increase. “Electricity, labour and fertiliser costs have all gone up. Last year, we would have paid around €190,000 for fertiliser and we’re expecting to have to pay €400,000 for the same amount this year,” he said. He has warned he will go out of business if prices do not rise: “Part of it is they want to see if they can bring in the same vegetables cheaper from Scotland or Holland.” Relations with buyers are poor: “A lot of them would cut you as soon as look at you and it’s all a bit sinister and horrible to be honest. I genuinely believe that there will be shortages on the shelves this year. “I don’t know where the retailers are thinking they can get Irish vegetables in the future if they’re driving growers out like this.” He said pledges by Minister for Agriculture Charlie McConalogue have done little to help. Imports already feature heavily. Over 60,000 tonnes of apples and 47,000 tonnes of onions are imported annually, while 72,000 tonnes of foreign-grown potatoes are bought, too. Despite talk of inflation, prices have fallen since 2013. However, the supermarkets defend themselves. Aldi Ireland’s group buying director John Curtin insists they have built “long-term, mutually beneficial relationships with our suppliers. Retailers drive organic growers out of businessCost pressures“Aldi is a committed supporter of both Irish growers and Irish food and drink producers, paying fair prices to all its Irish suppliers,” he said, adding that it is working with suppliers faced with significant cost pressures. The company’s focus on sourcing in-season Irish produce remained, he said: “We spent over €1 billion with Irish producers last year, an increase of almost 20 per cent on 2020, including €250 million on Irish food and drink [at Christmas].” Lidl was recently criticised by farmers for slashing the price of its organic range, but the company insists that the items listed in its weekly super saver deal “in no way impacts the price paid to suppliers”. Faced with pressures, more farmers want to go organic. Eleven growers, backed by the Irish Organic Association’s use of a European Union fund, saw sales rise from €3.8 million to €8.1 million over three years. However, bread tomorrow is not bread today, with growers complaining that supermarkets boast of paying their own employees the living wage, but leaving vegetable suppliers on the minimum wage. “I invested half a million euro into my business 10 years ago but if I had the same choice again today, I wouldn’t do it,” said one grower, who cannot be named to protect his relationship with his supplier. Back in Doneraile, Patrick Frankel knows there is a battle to convince a doubting public. Yes, he must cut costs, he says, but he must also teach people to grow their own vegetables. If only so they learn how hard it is to grow quality food. Source: Irish Times

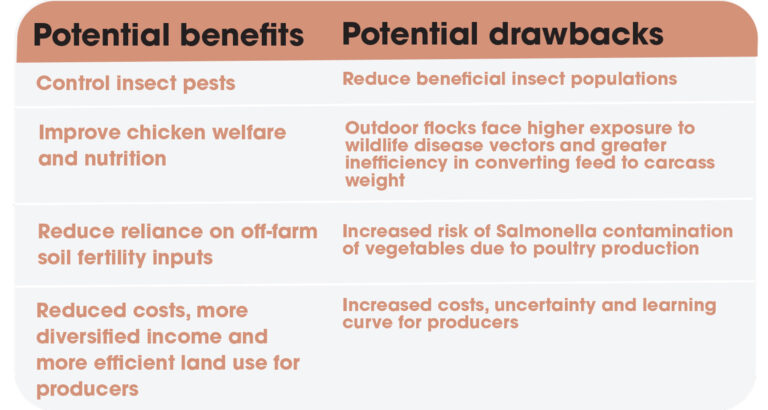

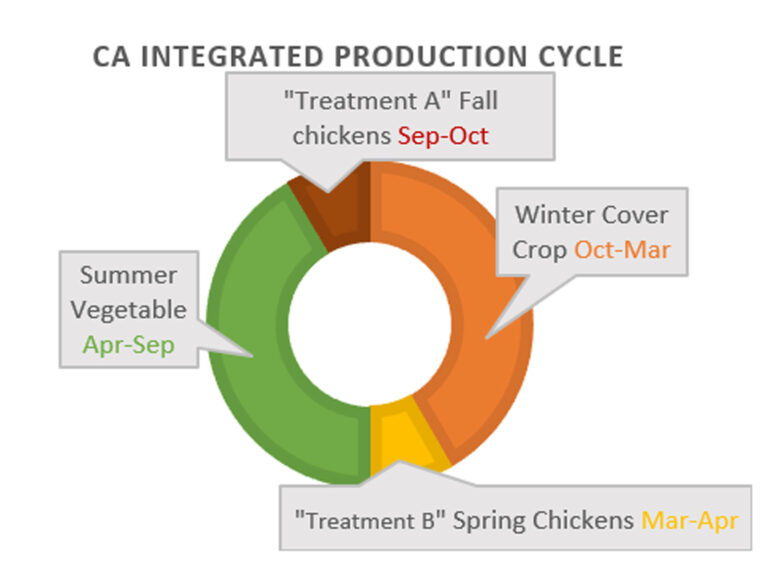

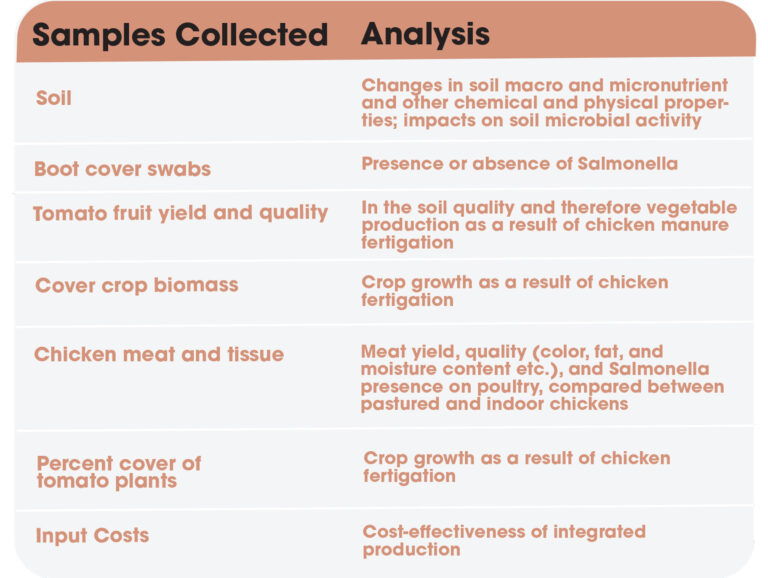

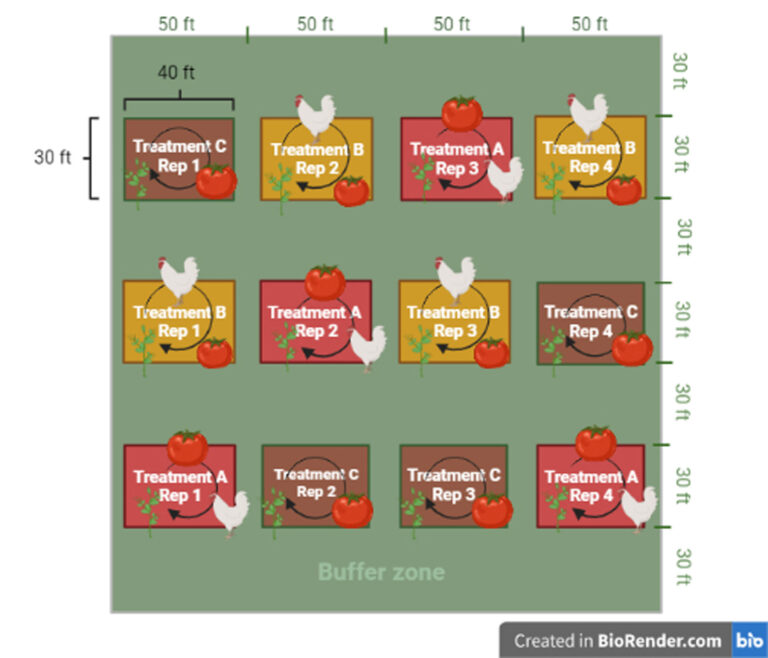

Olive tree growing deals with a tree of great historical, economic and environmental importance, which is why it is deeply rooted in the traditional habits of every producer. The organic cultivation of olive tree is based on methods of rejuvenation of the olive tree grove soil, the recycling of by-products and other available organic materials and the reproduction and protection of the natural environment. It is the method of olive production that aims to produce an excellent quality olive oil (meaning extra virgin olive oil), free from pesticide residues, which undermine health, and reduces contamination of soil, water and air. It also contributes to the preservation of the diversity of valuable plants of the area, wild animals and genetic material of the olive tree. Creation of an organic olive tree grove Suitable location: Before creating or setting up a new organic olive tree grove, it is necessary to study and take into account the soil-climatic conditions of the area. Locations with limited sunshine, long periods of shading and frost-affected areas should be avoided as much as possible. Coastal areas and areas with cool weather and high relative humidity, especially during the summer and autumn months, should not be preferred, because such areas favour high infestations from Olive fruit fly (Thakos (Δάκος) in Greek). It is also very important the principle that the location where the organic crop will be planted should not be affected or neighboured by conventional olive groves. In a sloping location protection measures must be taken against the transfer of rainwater from conventional olive groves or other conventional crops. Also, if possible, the plantation should be isolated with a tall natural windbreaker, so that it is not affected by spraying that will be carried out in conventional olive groves or other crops. Selection of soils and measures for their correction The main concern of every olive tree grower is from the beginning of the conversion or planting of the organic olive grove to do all those actions to significantly improve the physical and chemical properties of the soil for normal nutrition and growth of trees. We must keep in mind that the soil is a living organism with a number of important biological processes that in turn can feed the olive trees. Heavily used and damaged soils, with a limited concentration of organic matter, do not help the olive trees to grow and perform satisfactorily. Boring and cohesive soils that retain enough moisture cause rotting in olive trees and reduce or inhibit the prevention of various nutrients. Soils poor in organic matter are corrected, either by adding organic matter or animal manure or by applying green fertilizer, which is done by incorporating in the soil a mixture of legumes (vetch, broad beans, peas, etc.) with grass plants, with the aim of increasing organic matter and nitrogen. Green manure is the cheapest method due to the advantages it provides both to the ecological system (non-dependence on the imported expensive system of organic matter), but also in terms of cultivation (competition with some weeds, etc.). Also, the addition of organic matter to the soil improves its structure, makes it easier to cultivate the soil from agricultural machinery and allows better absorption and retention of moisture. Olive grove installation and varieties The olive trees of the organic olive grove must be planted at regular distances. Dense planting does not help their normal ventilation. In sparse planting, the entire area of the land is not economically exploited. Olive trees are preferred to have a trunk of normal height to facilitate the necessary cultivation care and normal ventilation. The most suitable varieties for organic farming are considered to be those that are resistant to pests and diseases and are adapted to the soil-climatic conditions of each region. Varieties grafted on wild olives show resistance to soil diseases and develop a large root system. The olive varieties 'Koroneiki', 'Ladoelia' and secondarily 'Picual' show considerable resistance to enemies and diseases. Cultivation care Nutritional requirements of olive trees: Significant amounts of the main nutrients of nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium are removed from the olive grove every year due to the needs of the plant for vegetative growth and production. It is natural that when the quantities removed are greater than those available there will be a reduction in production unless these elements are supplemented. The amount of elements to be added to the soil of each olive grove depends on the type of soil, the available stocks, the cultivation practice followed (pruning, irrigation, etc.) and the production of the year. Consequently, it is not possible for anyone to come up with an ideal fertilisation strategy that applies to all conditions, but it can single out some general guidelines. The most important parameter is always the nutritional requirements of the crop, in this case the olive. The first concern is to replenish at least the nutrients removed by harvesting and pruning. It has been found that on average 100 kg of olives remove from the soil: 0.9 kg Nitrogen (N), 0.2 kg Phosphorus (P), 1.0 kg Potassium (K) and 0.4 kg Calcium (Ca). An amount of nutrients that are trapped in the soil, in non-digestible form (mainly in Phosphorus and Potassium) or even lost by rinsing to the lower layers of the soil, mainly in Nitrogen, must be taken into account. Fertilization methods The fertilization of the organic olive grove aims at the improvement of the soil productivity and the strategy that ensures long-term improvement of the texture and structure of the soil along with the increase of its fertility. Olive fertilization should be based on a program to maintain and rejuvenate the soil of the olive groves. This program is mainly based on the application of the method of green fertilization with legumes, grasses or mixtures, the addition of compost from organic materials, as well as the addition of animal manure, which necessarily comes from animals primarily organic or even extensive breeding. Organic fertilization: An economical and practical way of fertilizing the organic olive grove is the preparation of compote using the plant residues of the olive grove with manure from organically or extensively farmed animals. One way to make organic compote is to use olive leaves from olive mills along with about 10-20% of sheep and goat manure. The construction of this type of organic compote costs money, so it is usually used in the first 3-4 years of conversion of the olive grove into organic. In the following years, olive leaves and other plant residues can be used together with 20-40% oil extracts from the tanks of the oil mills. It is well known that mill waste has a good content of various nutrients, organic matter and microorganisms. The best time to place the compote is immediately after harvest. For every tenth, an average of 2 cubic meters of compost is recommended. The fertilization is supplemented with the integration of the natural vegetation of the olive grove, with the integration of the leaves and branches up to 5 cm thick that are crushed by the cultivation, with the use of special mechanical tools-crushers, as well as with the use of the effluents of the olive mills. Part of this article can be found on gargalianoionline.gr (News from Messinia on time) Integrating Chicken and Vegetable Production in Organic Farming Chicken and tomatoes are a tasty duo beloved by many in popular dishes like chicken tikka masala and chicken cacciatore. This combination, delightful in the culinary sense, is also the subject of a recent integrated farming experiment. This fall, researchers at UC Davis harvested the first crop of tomatoes from a 1-acre experimental field and successfully processed the second flock of 130 broiler chickens. This acre is part of a tri-state experiment also taking place at University of Kentucky and Iowa State University, where the experiment was originally spearheaded by horticulture professor Ajay Nair. Funded by USDA, this research aims to produce science-based learnings and best practices for organic agricultural systems that integrate rotational production of crop and poultry together on the same land. Potential of Integrated Production While the idea of chickens alongside crops evokes an image of “traditional farming”, these systems are relatively rare in North America today. Integrated farms have the potential to help organic farmers create a more resource-efficient “closed-loop” system. For vegetable farmers looking to start an integrated system, chickens require the lowest startup costs as compared with other livestock. This type of diversified production may be especially promising given the growing consumer demand for more sustainably and humanely produced chicken. However, there are many beliefs that remain unconfirmed and questions that remain unanswered by scientific research when it comes to integrating poultry production into vegetable cropping. For instance, at what extent does manure deposited by poultry on the farm reduce the need for off-farm soil fertility inputs? What benefits can we observe when crop residue is used to supplement the diets of the chickens? What stocking rate is the most advantageous in these systems? What types of crops and breeds of chicken work the best with poultry production in different regions? And is it feasible to squeeze in a successful yield of broiler production into the transition window between different crop seasons? Finally, can all this be done effectively from a food safety perspective and economically from both a farmer and consumer level? Study Design To better understand and evaluate the potential to integrate poultry with crop farming from multiple perspectives, the research objectives focused on evaluating growth yields, quality of agricultural outputs, food safety risks, agroecological impacts on soil and pests, and economic feasibility of such systems. In this experiment, broilers were raised on pasture starting at around 4 weeks of age to graze on crop residue. In the California iteration of this experiment, we raised two flocks per year in between rotations of vegetable crops in the summer and cover crops in the winter (Figure 1a). Rather than remaining in a fixed location, the pastured broilers are stocked in mobile chicken coops, commonly referred to as “chicken tractors”, which are moved to a fresh plot of land every day for rotational grazing. Four subplots distributed across the field are grazed by chickens before vegetables are planted in the spring (treatment B), and four different subplots are grazed by chickens after vegetable harvest (treatment A). The impacts of grazing on soil and crop production of the two treatments are compared to a third control treatment of only cover crops and vegetables (treatment C), while the impacts of rotational grazing on meat production are compared to an indoor control flock. Collaborating researchers in Iowa and Kentucky are also collecting weed and insect diversity data to better understand the impacts on crop pests and better understand how poultry affect the integrated farmland. Additional studies on animal welfare for the chickens as well as conducting cultivar trials on the success of varieties of different vegetables like lettuce, Brussels sprouts, butternut squash and spinach tested in combination with poultry are being conducted. Challenges Identified and Lessons Learned As the study is still underway, we cannot make any conclusions without testing and re-testing experimental results to confirm their repeatability and statistical significance across more than one growing season. So far, however, we’ve collected a great deal of initial learnings on our integrated systems. Soil Fertility Organic farmers know that soil amendments, such as chicken manure, release nitrogen slowly to crops over time. Factors related to timing of application, precipitation and temperature affect how soil microbes process organic material to ultimately impact the soil quality. In California, although our tomato crop received sufficient subsurface drip irrigation, we suffered low yield and tomato end rot across the treatments. This was due to the fact that our experimental plot was previously conventionally managed and very nutrient depleted, an issue which we attempted to manage by applying organic compost and liquid fertilizer to the entire field to supplement the manure deposited by the chickens. In addition, severe drought during and after the period of manure deposition may have hindered soil microbial activity and, in turn, retarded the decomposition of our cover crop residue and chicken manure into the soil. Meat Production Additional data remains to be collected on subsequent flocks and statistical analysis on the findings have yet to be conducted before conclusions can be drawn. Preliminary results from meat quality analysis indicate that the pasture-raised chicken yielded less drumstick meat than the indoor control and breast meat was darker and less yellow in color. They also yielded redder thigh meat and less moist breast meat than the indoor chicken when cooked. So far, broilers in California that grazed on cover crops in the spring reached a higher average market weight relative to indoor control, while broilers grazed on tomato crop residue in the fall reached a lower average market weight relative to the indoor control. Food Safety No presence of Salmonella has been detected thus far in the soil nor on the poultry produced in the California experiment. Collaborators in Iowa and Kentucky report that persistence of Salmonella associated with the poultry producing soil has not been observed to persist into the harvest period. While these results are promising, it should be noted that Salmonella are relatively common in poultry. Ideally, best practices can be identified that reduce the risk of Salmonella persisting in the soil environment while crops are grown following chicken grazing. Many other anecdotal findings have emerged: In Iowa, a farmer collaborating with researchers to conduct their own on-farm iteration of the experiment has noted positive results from the poultry treatment on their spinach crop; our collaborating researchers also report that the chickens may appear to be eating an insect that is beneficial in their agricultural system, a finding which, if validated, may debunk the perception that their presence on the farm is always advantageous to pest control. In California, we are realizing the impact the design of the chicken tractors has on labor demands. Our 5 x 10 ft-wide wheeled coop was more difficult to move in a tomato production system with raised beds and loose soil as compared to a relatively more even and firm ground in a pasture. It seems apparent that engineering considerations such as wheel type, coop material and coop weight will influence the adaptability of poultry and crop integrations. Careful timing and planning is yet another labor consideration when it comes to transitioning successfully between cropping and poultry husbandry that we encountered. Eagerly, we await to gather more information in the next year until additional conclusions to our research questions can be drawn after the study concludes in 2022.

Additional Resources Nair, A. & Bilenky, M., (2019) “Integrating Vegetable and Poultry Production for Sustainable Organic Cropping Systems”, Iowa State University Research and Demonstration Farms Progress Reports 2018(1). Source: Organic Farmer Magazine  The chief scientist for The Organic Center says organic farmers shoulder most of the burden when pesticides drift from a neighboring farm. Jessica Shade says organic farmers have little recourse when there’s off-target movement of pesticides being applied on conventional acres. “It’s been stressing their relationships with neighbors (and) costing them money, but also costing them a lot of time. So there are a lot of things that don’t get quantified.”

Speaking to Brownfield at the Iowa Organic Conference in Iowa City Monday, she says the Organic Center is working to change that. “We’ve been doing a national survey to really understand what farmers are experiencing, what strategies they find that work and what they think isn’t working.” Shade says testing methods need to be improved because a large percentage of organic farmers don’t trust the process and think it’s too expensive. Source: https://brownfieldagnews.com/news/organic-crop-farmers-find-pesticide-drift-contentious-and-costly/ FOS Squared introduction and commenting Organic food producers and farmers are in serious trouble. Their depedence on the organic seeds continues on the same way as their depedence on pesticides and in US on the carcinogenic GMO crops as Bayer (which bought Monsanto) enters the market. World food supply enters a global tragedy period. Organic Food Is Finally Big Food, Large Enough Monsanto Got Into It Organic food is a $120 billion industry, and while that's a tiny fraction of regular food it is large enough that companies like Chipotle and General Mills have tried to gain traction. But a large seed company? That is new. Bayer, secretly now Monsanto (as anti-science activists love to claim in their conspiracy tales), is rolling out organic-certified seeds. This is not as difficult as it sounds. To be certified organic, you only have to not use newer pesticides or genetic modification, anyone who claims they use no pesticides or genetic engineering thinks you are gullible. So GMOs can't be organic, for example, but over 2,000 products have been created using the predecessor of GMOs, Mutagenesis, and all of them can be considered organic even though they were mutated using chemical baths and radiation. You can create huge amounts of nitrogen run-off using older copper sulfate pesticides and be organic, you just can't use safe neonicotinoids. Organic industry trade group have done a terrific job. First, they got their lobbyists and trade reps on a panel inside USDA that defines what "organic" means and keeps them exempted from USDA standards. So the dozens and dozens and dozens of exemptions for synthetic products or additives while still calling yourself organic has led to a lot of products being labeled organic. Non-GMO product has over 60,000 such products even when there is no GMO version. With such a large market in places like the US and Europe, it was only a matter of time before a large company wanted a piece of that pie, and Bayer is getting in. Starting next year you can buy organically produced seeds for tomato, sweet pepper and cucumber. But don't worry, those won't say Monsanto, they will be under the Seminis and De Ruiter brands. Source: Science 2.0 Extrait d'article en Français

Les producteurs d'aliments biologiques et les agriculteurs sont en grande difficulté. Leur dépendance vis-à-vis des semences biologiques se poursuit de la même manière que leur dépendance vis-à-vis des pesticides et aux États-Unis vis-à-vis des cultures OGM cancérigènes lorsque Bayer (qui a acheté Monsanto) entre sur le marché. L'approvisionnement alimentaire mondial entre dans une période de tragédie mondiale.  Organic food is no longer a niche market. Sales of organic food products in the European Union have more than doubled over the last decade - from €16.3 billion in 2008 to €37.4 billion in 2018 - and demand continues to grow. However, many Europeans are still unsure of what "organic" really means. Is it natural? Free of pesticides? Locally grown? Well not exactly. Here are some of the conditions food products must meet in order to be considered organic in the EU: No synthetic fertilisers Natural fertilisers, such as compost and seaweed derivatives (and animal manure), are essential to maintaining fertile and healthy soil. So organic food must be grown with these products, rather than synthetic fertilisers that are used in conventional farming, and which tend to be made of harsher chemical ingredients including nitrogen compounds, phosphorus, and potassium. "Organic farming improves soil structures and quality and enhances biodiversity. Studies have shown that organic farming present 30% more of biodiversity in the fields", explains Elena Panichi, Head of Unit at DG Agriculture and Rural Development (DG AGRI). No synthetic pesticides Farmers need to fight weeds and pests. Organic farmers are only allowed to use naturally-derived pesticides, made from plants, animals, microorganisms, or minerals. "These chemicals are of a natural origin. For instance, essential oils, plant extracts, that are listed in the relevant regulation, and are authorised, following a process that implies a scientific committee to assess the effect on the environment", says Panichi. Organic farms also have techniques such as crop rotation, or planting different crops on the same plot of land, to help to prevent soil-borne diseases. Natural predators, such as ladybugs, can also be an effective method of pest control. However, it is important to remember that just because something is “natural”, it doesn’t automatically make it harmless to either people or the environment. No GMOs (No genetically modified organisms/ingredients/crops/foods/animals) To be certified as “organic”, food cannot contain products made from genetically modified crops. This rule is the same for organic meat and other livestock products. Besides, the animals are to be raised on 100% organic feed. Antibiotics as a last resort The animals we eat, or whose products we consume, need to be kept disease-free. Many conventional farmers routinely use antibiotics for disease prevention. These can end up making their way into the food chain. Excessive antibiotics are not good for people or animals because they can help create superbugs. Antimicrobial resistance is a global concern. Every year, around 33, 000 people die in the EU, due to infections from antibiotic-resistant bacteria. On organic farms, the use of antibiotics is severely restricted. Farmers control disease by limiting the number of animals they raise and using methods such as a healthy diet for their livestock. They are only allowed to use antibiotics when absolutely necessary for an animal's health, in order to avoid suffering, and when natural remedies such as phytotherapeutic and homoeopathic medicines are not effective. "If in conventional [farming], sometimes antibiotics are given as preventive tools, in organics, antibiotics can be given as a last resort if there are no other methods to intervene. Normally, the higher animal welfare standards applied in organics already keep animals in a healthier status that prevent the use of antibiotics", explains Panichi. However, studies have shown that antibiotic use on farms is on the decline. Sales of animal antibiotics in the EU have fallen by more than 34% between 2011 and 2018. Better animal welfare Organic farmers must provide the environmental conditions necessary for animals to express their natural behaviour, such as adequate outdoor space. This is not compulsory in conventional farming. There are additional rules such as the prohibition on caging or mutilation unless absolutely necessary for health reasons. What "organic" doesn't mean locally grown. Europeans are the second largest consumers of organic in the world. Local supply can’t meet demand yet, so a large number of organic products are imported. China, Ukraine, Dominican Republic and Ecuador are the main EU trade partners for organic food imports. "Green" packaging Words like “natural”, “green” or “eco” on labels and packaging do not necessarily mean a product is organic. Healthy There's a wide range of organic product on supermarket shelves, from burgers to pizzas, from cheese to wine. The health implications of consuming excess fats, salt or sugar don't disappear just because a food product is organic. Too much fat, salt and sugar is still bad for you, whether it is organic or not. How can you be sure that the “organic” food you’re buying is actually organic? The most reliable way to know if a product is organic is if it has this official EU logo. The white leaf on a green background means that EU rules on production, processing, handling and distribution, have been followed and that the product contains at least 95% organic ingredients. This logo can only be used on products that have been certified by an authorised control agency or body. Some countries have also created their own organic logos. They are optional and complementary to the EU's leaf. This is the French one, for instance. Words like “natural”, “green” or “eco” on labels and packaging do not necessarily mean a product is organic.New rules coming in 2022 EU rules on organic production will change soon. In 2022, Europe will have legislation with stricter controls. Panichi believes it will bring a "substantial improvement" to the organic sector. "We have to bear in mind that the new organic legislation is not a revolution, but it's an evolution of the organic legislation that started in the past years and has been kept evolving together with the sector". The new legislation will harmonise rules for non-EU and EU producers. It will also simplify procedures for small farms in order to attract new producers, thanks to a new system of group validation. The list of organic foods is expected to grow, with the addition of products such as salt and cork. The possibility of certifying insects as organic is also expected in the rules. What is the future of organics? "Surfaces in Europe are increasing or as well as all over the world, and they are increasing at a fast pace," says Panichi. As part of its Farm To Fork strategy, the EU has committed to increasing organic production, with the goal of 25% of all agricultural land being used for organic farming by 2030. In 2019, it was only around 8%. By 2030, Europe also aims to reduce the use of harmful chemicals and hazardous pesticides by 50%. Buying organic food is still too expensive for many. One of Farm To Fork's main goals is to make healthy, sustainable food more accessible and affordable to all Europeans. A French from 2019 shows that a basket of eight organic fruits and eight organic vegetables is, on average, twice as expensive as a basket of non-organic products. Source: Euronews Pictures: Source for Organic Leaf picture is Euronews and European Commission is for Farm to Fork picture Qu'est-ce qui rend les aliments biologiques « bio »?

Extrait d'article en Français - Pour être certifiés « biologiques », les aliments ne peuvent pas contenir de produits issus de cultures génétiquement modifiées. - Pas de pesticides de synthèse. - L'agriculture biologique améliore la structure et la qualité des sols et renforce la biodiversité. - Des mots comme « naturel », « vert » ou « éco » sur les étiquettes et les emballages ne signifient pas nécessairement qu'un produit est biologique. Increasingly popular with consumers, Washington-grown organic apples and pears thrive in the region’s dry, disease-discouraging climate. Off the tree, however, organic fruits are at the mercy of physiological disorders and fungi that can rot and destroy more than a third of the annual harvest before it gets to the table. This fall, scientists at Washington State University are launching new research to find safe, organic-friendly ways to defeat post-harvest diseases and foodborne illnesses in apples and pears, while extending their storability. Achour Amiri, a Wenatchee-based plant pathologist, is partnering with a team of scientists and students, including food safety and postharvest systems specialists, to test promising technologies using heat and controlled atmosphere in storage. Funded by a four-year, $1.5 million grant from the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture’s Organic Agriculture Research and Extension Initiative, the team is also exploring safer fruit coatings and timely sprays to limit infection and preserve organic fruit quality. Heat after harvest Growers currently utilise some organic treatments to keep fungi at bay in the orchard. “Once the fruit is harvested, it’s a different story,” Amiri said. Organic packers lack effective methods to stop postharvest pathogens and physiological disorders. Rots are their number one challenge to packing and storing fruit,” he added. “After five months, they can lose up to 50% of the crop just to rot.” Thermotherapy, or heat treatment, is one alternative. High temperatures shut down and kill microbes, including decay-causing fungi. Thermotherapy has also been shown to keep fruits and other produce fresh longer. “We need to find the optimal temperature to keep fruit quality and kill spores without damaging the fruit,” said Amiri, who will test heat’s effect on major fungal culprits, such as gray mold, bull’s eye rote, speck rot, and blue mold. Apple, pear, and stone fruit varieties may have varied susceptibility to heat, so the team will test different cultivars to learn how to use thermotherapy safely. Dynamic controlled atmosphere

Another approach involves changing the controlled atmosphere in which apples and pears are stored. Traditionally, temperature, humidity, and levels of oxygen and carbon dioxide are steadily maintained to slow the ripening process and keep fruit fresh. Amiri’s team is testing a modified practice called dynamic controlled atmosphere storage, in which oxygen levels are progressively lowered. “We’re hoping to show evidence that this can work in reducing decay and extending fruit quality,” Amiri said. Fruit gives off gasses in storage. Scientists can analyze these exhalations to learn if fruit is under stress, which affects freshness and firmness and can cause other disorders. Amiri seeks to find the limit before stress begins. Better timing and ingredients The team will also test different spray materials made of biological agents, such as beneficial bacteria, and other safer ingredients that may combat rot-causing microbes. “Different pathogens infect fruit at different stages of the production cycle, so timing is key,” said Amiri, who plans to test ingredients through the seasons to choose the most effective approach, as well as define the best harvest window for quality and disease defense. Starting field work next spring, he’ll partner with packers and farmers to ensure discoveries work in the real world. Amiri is excited by the cross-disciplinary nature of the project, which connects experts in pathology with fruit quality, physiology, and food safety. “We want to develop these technologies to cover other issues beyond rots, preserving fruit quality and improving safety,” he said. Source: WSU Insider Photos from: Anita Jankovich Unsplash-Rotten fruits and Organic ekiosk: Live Different, Go Organic-Organic Oranges The some other alternatives to keep fruit safe from fungi-Such case is the Organic Sundried Kymi Figs which are presrved using a bay leaf and they do not contain sulphur chemical compounds for preservation. If you would like to taste these delicious Kymi Figs follow the link on the Organic ekiosk: Live different, Go Organic We instinctively know that the label “organic” means better. But do you know why organic farming is better, who benefits from it and how it helps the environment? What is organic farming? Organic farming is centred around the idea that farming should be a part of the natural cycle. It doesn’t exploit the soil but enriches it, keeps it alive, protecting biodiversity, while making farming sustainable. It is a farming system that uses only natural fertilizers and environmentally friendly methods of pest, weed and disease control. When it comes to plant foods, it means the crops are grown without the use of synthetic fertilizers, dangerous pesticides, genetic modification (GM) and ionizing radiation. Organic farming relies on principles such as crop rotation, crop residue utilisation, composting, less mechanical and more manual labour. Organic foods don’t contain chemical preservatives. They aren’t coated in synthetic wax (e.g. citrus fruit) and don’t contain synthetic colourants or flavourings. That means not just that they are healthier, it also means they are fresher because they don’t have a long shelf life. Organic crops contain no or only tiny amounts of chemical residues. They have more antioxidants and some other nutrients, richer flavour, are safer for people with food sensitivities. They are also less likely to cause adverse reactions (due to the lack of chemicals in them) ref 1. How is organic farming more sustainable? Organic plant cultivation is great for the environment because it doesn’t pollute, it increases soil fertility, reduces soil erosion and protects wildlife. That way, it ensures the land can be used for generations to come without exhausting the natural resources in the area. One of the features of organic farming is cultivation of naturally more resilient crops that can ensure a reliable food supply. The organic standards mean that farm workers and people living in the area are not exposed to dangerous chemicals, which supports their health. That’s also a key part of sustainability. How does organic farming support wildlife and biodiversity? Synthetic pesticides, herbicides and other chemicals don’t just kill the unwelcome plants (weeds) or insects, they kill a number of species that are important to maintaining balance in nature. The poster species for the devastating effects of some industrial pesticides are bees. When bees die, our entire food supply will collapse because bees are the main pollinators ensuring successful crop yields. Yet it’s not only about bees. Organic farming also protects thousands of other insect species, hedgehogs, birds, bats, frogs and fish. It doesn’t poison them and their environment. Another big factor is that organic farming supports wildlife by maintaining hedgerows, ponds and woodlands. Synthetic fertilizers can pollute streams and ponds, throwing the whole ecosystem into disarray and causing problems such as algal bloom. When that happens, algae reproduce at a rapid pace, covering entire water surfaces and suffocating fish who live there. This simply doesn’t happen with organic farming! But that’s not all. By avoiding GM, organic farming also protects local species from introducing foreign genes into their populations. It’s true that some GM plants are safe but we still don’t have enough data to be certain of long-term effects of GM on native species and the environment. Organic foods don’t contain chemical preservativesWhy does organic farming use less energy and release less carbon emissions? According to the longest organic versus conventional farming comparison study (ref 2), organic farming uses 45 % less energy and releases 40 % less carbon emissions. Simply not using nitrogen fertilizer in organic agriculture saves huge amounts of oil used for its manufacture and transport. It also saves a lot of emissions as nitrogen fertilizers produce nitrous oxide – a powerful greenhouse gas. Another saving comes from organic farming relying more on manual labour rather than the use of machines and utilising local resources more thoroughly and efficiently. Growing organic crops also results in greater carbon sequestration. More carbon dioxide is captured and stored in the soil as carbon. This is a major advantage as not only it means that more carbon dioxide is sucked out of the air, it also means better soil quality. A large study showed that the best land management practices in organic farming can increase the amount of carbon locked in the soil by 24% (ref 3). Lastly, organic soil holds more water. That, of course, helps to conserve water but it also means organic crops are not as severely affected by dry weather as conventionally grown crops. Could the world’s farming ever be 100% organic? Organic farming requires more land than conventional farming to produce the same amount of food. Without chemicals, the yields and harvests are 10-20 % smaller (ref 4) . This begs the question whether we could feed everyone on the planet if all our farming was fully organic. A team of researchers modelled various food production scenarios. They came to the conclusion that the world population could be fed entirely through organic farming and without any deforestation but only under one condition. If we all go vegetarian (ref 5). Are there any disadvantages of organic farming? That depends whether we talk organic animal or plant farming. When it comes to plants, more manual labour and smaller yields make organic produce more expensive. Some argue that the energy and emission savings are not that big in organic farming because we need more land than non-organic farms to produce the same amount of food. Yet, organic farming has so many benefits that they still outweigh the need for slightly more land. Organic animal farming is usually a little better in terms of animal welfare. But because organic standards are meant to mainly protect the consumer and the environment, it’s often the animals who pay the extra price. It’s because the use of antibiotics and medication in general is severely restricted. So some animals may actually suffer more or for longer when they fall ill. Is buying local and seasonal produce more or less important than buying organic? Of course, if you can buy local, seasonal, organic produce, that’s the absolute best scenario! If that’s impossible, it may help to organise your decision-making into steps. Is the food organic but from the same continent? That may be the next best choice. Is the food organic and from the other side of the world? Then it depends on your priorities. Your health versus emissions caused by transport but you may also want to factor in how often you buy it. If it’s an occasional treat, it’s probably still a good choice. If it’s your staple, it may be better for you to look for a more local alternative. There’s no easy answer but the best policy may be to buy organic whenever possible and not beat yourself up when it’s not. Have you ever wondered what would happen if the world went vegan? This is what our future would look like if plant-based farming became widespread. References 1. Crinnion WJ, 2010. Organic foods contain higher levels of certain nutrients, lower levels of pesticides, and may provide health benefits for the consumer. Altern Med Rev. 15 (1): 4-12. 2. Rodale Institute. Farming Systems Trial. Available at: https://rodaleinstitute.org/science/farming-systems-trial/ 3. Crystal-Ornelas R, Thapa R, Tully KL, 2021. Soil organic carbon is affected by organic amendments, conservation tillage, and cover cropping in organic farming systems: A meta-analysis. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment. 312: 107356 4. Reganold JP, Wachter JM, 2016. Organic agriculture in the twenty-first century. Nat Plants. 2:15221. 5. Erb KH, Lauk C, Kastner T, Mayer A, Theurl MC, Haberl H, 2016. Exploring the biophysical option space for feeding the world without deforestation. Nat Commun. 7:11382. Source: Food & Living Vegan Photos from: Food & Living Vegan |

Archives

January 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed