|

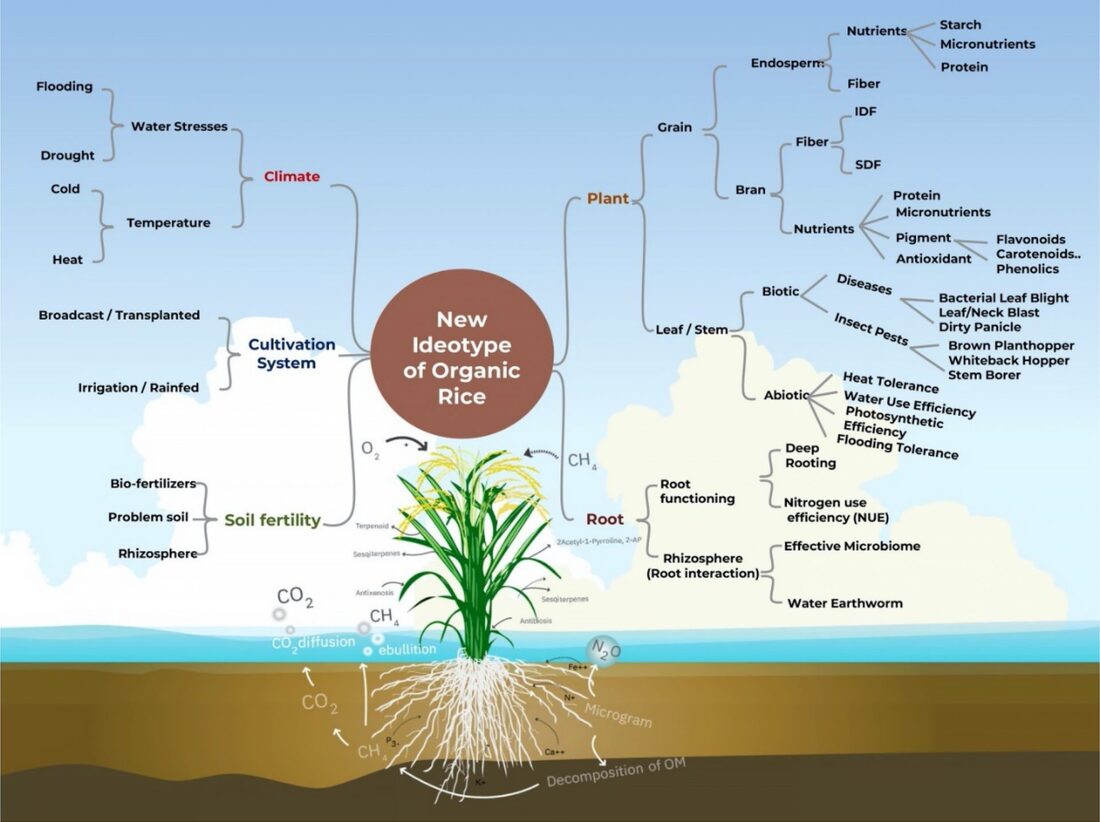

Professor Apichart Vanavichit, PhD, Rice Genomic Breeding Expert at Rice Science Center, heralds the next green revolution of organic riceRice is a major food crop for more than half of the world’s population and a crucial export commodity for Thailand. Despite the success story of the first Green Revolution in 2005, new rice varieties developed in Thailand negatively impact the environment and well-being of rice farmers in irrigated areas. On the other hand, based on chemical-free cultivation practices, organically grown rice conserves the environment and genetic diversity, and enhances the nutritional properties of harvested rice. Nevertheless, grain yield generally makes up half of chemical-rich irrigated rice. Most importantly, the lack of resistance to diseases, insect pests and environmental stressors makes organic rice vulnerable and risky for crop loss. As a result, rice prices are significantly higher, with lower outputs from organic cultivation than non-organic rice. However, significantly increased productivity and enhanced resistance in organic cultivation sustain organically-grown rice and benefit consumers by reducing the market price. Breaking the plateau of grain yield in organic rice is a grand challenge for rice breeders to comprehend any limitations and provide genetic solutions to enhance the efficiency and productivity of organically-grown rice. One approach involves the high genetic diversity of Indica x Japonica crosses to maximize heterosis, the genetic phenomenon when progenies outperform their parental lines in grain yield and productivity. The recent gathering of rice scientists and breeders around the world at the 19th International Symposium on Rice Functional Genomics in Phuket, Thailand reports an understanding of precision breeding for organic rice. New ideotypes of organic rice breedingWe have designed a new rice ideotype to fit into organic cultivation. The key features are high productivity, high water and nutrient use efficiency WUE, intermediate plant height, intermediate maturity, strong stem, resistance to all biotic and abiotic stresses, resiliency to climate change and pyramiding. All resistance genes in elite rice varieties are achieved by pyramiding into existing nutrient-rich rice, high-yielding cultivars with good broad-spectrum resistance to both diseases and insect pests, tolerance to abiotic stresses, improved agronomic traits, increased photosynthetic efficiency and enhanced interaction with microbiota. Climate-ready, nutrient-rich riceThailand Rice Science Center has relentlessly developed the first four rice models for organic farming since 2000 until today. We have undertaken four organic breeding programs selected under organic cultivation systems: Super Riceberry-Rainbow Rice, Super Low GI White Rice, Super Jasmine Rice and Super Waxy Rice. Our main goal is to choose new rice varieties to significantly outperform local varieties of the same quality type under high pressure from diseases and insect pests in multiple target organic areas. The ultimate goal is to maximize yield and quality under optimum organic agricultural practices. To conclude, 50 rice varieties have broad-spectrum resistance to bacterial leaf blight, leaf blast, brown planthopper, and tolerance to flooding, extreme heat, salinity, acid sulfate soil and drought. In addition, rice varieties with improved water use efficiency, resistance to sheath rot, brown spots, and bacterial leaf streak have recently developed. These innovative rice varieties are key success stories of the green revolution in organic rice. Rhizosphere-microbiome interaction – key to productivityDespite no addition of chemical fertilizers, rice can be pretty productive under organic cultivation, albeit with lower grain yield in many cases. Nature’s secret depends on the genetic makeup of rice and soil microbiome. The rhizosphere and the soil environment near the rice root surface are crucial interfaces for water and nutrient absorption, releasing root exudates and interacting with soil microbiota. Gaseous exchange between roots and microbial community occurs here, enabling methane to escape from submerged soil to the atmosphere and become a greenhouse gas. The rice rhizosphere accommodates large numbers of microbial communities, including endophytes, rhizosphere bacteria and fungi. However, the intensive application of N-P-K fertilizers adversely affects the abundance and diversity of the microbial community in the rhizosphere responsible for nitrification, N2 fixation, and tolerance to problematic soil. On the other hand, the main advantage of organic rice cultivation is more diversity of soil microbiota associated with rice rhizosphere. Recently, there have been reports on PGP and plant growth promotor microbes, including endophytic stenotrophomonas and Piriformospora indica. To conclude, we have detailed the success story of organic rice breeding by precision rice breeding involving multiple gene pyramiding to generate sustainable, productive, nutritious rice varieties that are resilient to climate change. Acknowledgement This project was supported by the BBSRC Newton Rice Research Initiative BB/N013646/1, National Science and Technology Development Agency (NSTDA) (Grant No. P-16- 50286), and NSRF via the Program Management Unit for Human Resources and Institutional Development, Research, and Innovation (Grant No. B16F630088). The next green revolution of organic rice

Article for organic source: https://www.openaccessgovernment.org/article/green-revolution-organic-rice-yield-environment/149446/ Richer in nutrients and dietary fiber, organic food would also reduce exposure to pesticides. Interview with Denis Lairon, nutritionist and research director emeritus at Inserm (National Institute for Health and Medical Research). According to the Barometer of the perception and consumption of organic products published in March 2022, 9 out of 10 French people consume organic (91%). What is the impact of this diet on health? Answers with Denis Lairon, nutritionist and research director emeritus at Inserm (National Institute for Health and Medical Research). Eating organic would be better for your health. Is it true ? Organic foods are better in terms of nutritional values. It is noted that in vegetable products, there is less water, especially for vegetables. According to studies, we also notice that there is more magnesium, iron and zinc. Consumers of organic products also have a better diet. For example, they choose more cereals made from brown or wholemeal flours, and pulses, which are rich in nutrients, minerals and dietary fibre. This has a major impact on their nutritional status. We observe that those who regularly eat organic have significantly higher nutritional intakes than those who never eat organic. Organic enthusiasts are also less inclined to buy animal products (meat and dairy products). Conversely, they consume twice as many fruits and vegetables, unrefined cereals... We also measure between 40 and 80% reduction in exposure to pesticides. Scientific work published with the NutriNet-Santé cohort since 2013 and by the BioNutriNet study also indicates that eating organic reduces the risk of obesity and overweight... In 2013, we worked on a sample of 54,000 adults at any given time. We have observed that among regular consumers of organic (about 60-70% of their food), the risk of becoming obese is reduced by 50%. In our second study, we followed 62,000 people over three years, and found that there was a 30% reduction in the risk of obesity and overweight. These results are confirmed by two other studies carried out worldwide, in Germany and the United States. What about other diseases? For cardiovascular risk, we studied the metabolic syndrome. It is characterized by abdominal overweight, hypertension and increased blood sugar. We found that there was a 31% reduction in the risk of having metabolic syndrome for people who regularly ate organic compared to those who never ate organic. For type 2 diabetes, 33,000 men and women were followed for 6 years. The overall result is a 35% reduction in the risk of having type 2 diabetes if you eat organic food regularly. The difference is much more marked in women than in men. Another study on 70,000 adults finally indicates a 25% drop in the overall risk of cancer among organic consumers. Source: See article for organic here

London’s food-growing schemes offer harvest of fruit, veg and friendship. Behind a row of local authority maisonettes in Islington, north London, on a sun-drenched Tuesday morning, the air hums with insects. Landing bees bend the stems of a patch of lavender as Peter Louis, 60, clears overgrowth with shears.“I come here in winter probably once or twice a week; in summer probably about two or three times a week,” he says. Louis lives alone and is out of work because of poor health. But at the project he can meet friends, and even when he doesn’t the work is a salve to his isolation. “Since the Covid lockdown I suffer from anxiety, stress and depression, and I’m a hands-on person: I have to do something, sitting at home won’t help me,” he says. “And at the end of the day I feel really good. It’s not because I might have fruit or veg to get out of it; it’s the fact that we’re doing this for everyone.” Islington is London’s most crowded borough: 236,000 people crammed into 5.74 sq miles. Land is scarce and expensive: Family homes with gardens change hands for £1m-plus, but almost a third of the borough’s households have no private outdoor space. Space is so tight Islington cannot meet its legal requirement to provide residents with allotments. It is hardly the ideal location for growing food. But for the past 12 years growing food is exactly what the Octopus Community Network has been doing here. The charity runs eight growing sites, located in areas of serious deprivation, and supports a number of other smaller initiatives. They offer access to nature, education and for socialising. And, when harvest time comes, produce is distributed to the community, providing fresh organic vegetables to families that struggle to afford them. On the Hollins and McCall Estate in Tufnell Park on Tuesday, at Octopus’s community plant nursery, six women are potting up vegetable shoots. The nursery, with a range of beds, a polytunnel, various composters and a shed full of equipment and supplies, is Octopus’s education and learning hub. “The beds are demonstrations of different kinds of growing techniques,” says Frannie Smith, the charity’s full-time community cultivator, overseeing the work. “Then the plants get given away to community groups across Islington to help facilitate their growing. Everything here is about making connections with people that want to be involved with urban food growing in Islington.” AdvertisementDaniel Evans, a researcher at the school of water, energy and the environment at Cranfield University, in Bedfordshire, says growing food in towns and cities can deliver ecosystem benefits, “which are much more than just about putting food on a plate”. Recently Evans worked with colleagues from the universities of Lancaster and Liverpool in scouring every single piece of research they could find on the benefits of farming areas in urban spaces. Vegetation of the right kinds are particularly good for sequestering carbon from the atmosphere, regulating microclimates, harbouring biodiversity, encouraging pollination, and restoring soils, they found. In some circumstances, green spaces can even mitigate natural disasters by, for example, absorbing flood water. “There are benefits also to humans, in what we call cultural services, things like recreation,” he says. People getting out into the allotment or community garden can often bring them not only physiological but mental health benefits as well. Often it allows them to interact with people who they wouldn’t necessarily live or work near, thereby kind of enhancing those societal relations and, for some of them, it’s a great opportunity to get, you know, spiritual experience, a sense of being in a green space, whereas most towns and cities are pretty much grey.” Smith finds a range of ways to get people involved. Members of the local Good Gym help carry deliveries of compost. Residents of a nearby halfway house for recovering addicts till the soil of a church garden alongside wealthy octogenarians. Soon, Octopus will begin a partnership with Mencap to teach disabled adults, as well as volunteers to work with them. But, as many social and psychological benefits as a scheme such as Octopus brings, the food growing can not just be an afterthought. “What we’ve seen in the last few years now is a real need to start thinking about local food growing, or at least sharing out the load,” says Evans. “The UK has a great reliance on food imports. The UK a couple of years ago was importing about 84% to 85% of food; about 46% of vegetables that are consumed in the UK are imported from abroad. “So, of course, when you have a crisis event, like a pandemic or like Brexit, that can really threaten supply. And so if you get local authorities or people growing in their local community together, just helping out producing fruit and vegetables for that local community, then you’re helping to lessen the severity of those shocks.” Eight-and-a-half miles south, across the River Thames, and 33 metres under the streets of Clapham, is an underground farm run by Zero Carbon Farms (ZCF) an entirely different kind of urban food-growing project, which says it uses 70% less water and a fraction of the space of a conventional farm. Evans says the future is probably a mix of the Octopus and ZCF models. “Because there’s quite an interesting paradox here. You get more people into a city, and then you’ve covered up all the soils for those residential buildings and you’ve not got anywhere to grow food any more. So we need to think quite creatively. This is where the hi-tech and digital might come in, about how we use some of these spaces to alleviate that issue.” But a project such as ZCF lacks key elements offered by Octopus, Evans adds. “The real question really here is how does it affect the individual life – you know, the individual urban dweller? “I think cases like the Octopus community – which is not hi-tech, it’s pretty accessible to all, it brings together a wide variety of people from the local neighbourhood – that is, in a sense, what creates sustainability, because we can’t always have experts and specialists doing these things on behalf of everyone,” he says. “We need to get the local community involved so that they in a sense help feed themselves and help sustain their own futures.” … we have a small favour to ask. Tens of millions have placed their trust in the Guardian’s fearless journalism since we started publishing 200 years ago, turning to us in moments of crisis, uncertainty, solidarity and hope. More than 1.5 million supporters, from 180 countries, now power us financially – keeping us open to all, and fiercely independent. Unlike many others, the Guardian has no shareholders and no billionaire owner. Just the determination and passion to deliver high-impact global reporting, always free from commercial or political influence. Reporting like this is vital for democracy, for fairness and to demand better from the powerful. And we provide all this for free, for everyone to read. We do this because we believe in information equality. Greater numbers of people can keep track of the global events shaping our world, understand their impact on people and communities, and become inspired to take meaningful action. Millions can benefit from open access to quality, truthful news, regardless of their ability to pay for it. Source: Guardian Patrick Frankel on a landscape where carrot price is the same as a vanilla shot in coffee Nestled in thick forests around Doneraile in north Cork, organic farmer Patrick Frankel has made a living for himself and his family from six acres of a market garden and four polytunnels. The focus on quality has worked, but Frankel is as concerned as every other vegetable grower in the State about the public and the supermarkets’ demand for lower prices, and the need to keep growers in business. “In a market where a normal bag of carrots will cost the same as a 50-cent shot of vanilla for a coffee, it should be easy to see how most vegetable growers are frustrated,” he said. Before Covid-19 struck two years ago, Frankel was supplying up to 30 restaurants with fresh vegetables. Hit by closures, he moved online with Neighbourfood, selling directly to customers. “When the lockdown started, we fell off a cliff with our restaurant customers but two weeks later we were up selling again thanks to Neighbourfood contacting us,” he said. “We sell mainly salad and charge €3 for a 125g bag. Consumers like that it’s chemical free. From operating our own market stall, I know it’s not just the middle class who care about buying local, organic food. “But I don’t know how to convey to consumers the time, effort and skill that’s needed in vegetable production. There’s a generational disconnect there.” Frankel has been in business for 16 years. He has had a few complaints that some of Doneraile farm’s vegetables “weren’t symmetrical, which is just harder to do in a small organic system”. Price vs qualityThe Irish eat a lot of fruit and vegetables, better than elsewhere in the European Union, while consumption jumped by a quarter during the pandemic’s home cooking “craze”, where more than €600 million was spent. However, the biggest driver is price, not quality. Nearly half of people say prices dictate whether a bag of vegetables is bought or not – all of which keeps the State’s 200 growers – and especially the 135 larger ones on tight margins. A one cent change is often the difference between profit and loss, say some growers. One, who did not want to be named, told of how he was “laughed out of the room” recently when he asked one supermarket for an increase. “Electricity, labour and fertiliser costs have all gone up. Last year, we would have paid around €190,000 for fertiliser and we’re expecting to have to pay €400,000 for the same amount this year,” he said. He has warned he will go out of business if prices do not rise: “Part of it is they want to see if they can bring in the same vegetables cheaper from Scotland or Holland.” Relations with buyers are poor: “A lot of them would cut you as soon as look at you and it’s all a bit sinister and horrible to be honest. I genuinely believe that there will be shortages on the shelves this year. “I don’t know where the retailers are thinking they can get Irish vegetables in the future if they’re driving growers out like this.” He said pledges by Minister for Agriculture Charlie McConalogue have done little to help. Imports already feature heavily. Over 60,000 tonnes of apples and 47,000 tonnes of onions are imported annually, while 72,000 tonnes of foreign-grown potatoes are bought, too. Despite talk of inflation, prices have fallen since 2013. However, the supermarkets defend themselves. Aldi Ireland’s group buying director John Curtin insists they have built “long-term, mutually beneficial relationships with our suppliers. Retailers drive organic growers out of businessCost pressures“Aldi is a committed supporter of both Irish growers and Irish food and drink producers, paying fair prices to all its Irish suppliers,” he said, adding that it is working with suppliers faced with significant cost pressures. The company’s focus on sourcing in-season Irish produce remained, he said: “We spent over €1 billion with Irish producers last year, an increase of almost 20 per cent on 2020, including €250 million on Irish food and drink [at Christmas].” Lidl was recently criticised by farmers for slashing the price of its organic range, but the company insists that the items listed in its weekly super saver deal “in no way impacts the price paid to suppliers”. Faced with pressures, more farmers want to go organic. Eleven growers, backed by the Irish Organic Association’s use of a European Union fund, saw sales rise from €3.8 million to €8.1 million over three years. However, bread tomorrow is not bread today, with growers complaining that supermarkets boast of paying their own employees the living wage, but leaving vegetable suppliers on the minimum wage. “I invested half a million euro into my business 10 years ago but if I had the same choice again today, I wouldn’t do it,” said one grower, who cannot be named to protect his relationship with his supplier. Back in Doneraile, Patrick Frankel knows there is a battle to convince a doubting public. Yes, he must cut costs, he says, but he must also teach people to grow their own vegetables. If only so they learn how hard it is to grow quality food. Source: Irish Times

This article mentions the difference between certified organic food and conventional food. It is important to mention that the organic food mentioned on www.soilandsun.co.uk is a certified organic food. Organic certification involves application of strict standards and an annual audit from an indepedent auditing on the application of these standards. Failing to follow these standards, farmer or grower are not allowed to trade their product as organic in other words they lose their organic certification status which proves that the product made by them is not anymore organic. A. Organic food are Heathy Organic foods are free from:

Organic foods have different appearances This difference mainly apply to fruits and vegetables. As a consumer you will see fruits with smaller size, cracks or blemishes on the surface. They do not look super shiny and do not have perfect shape but they look imperfect and real. Organic farming is environment friendly and sustainable Due to absence of these toxic pesticides, heavy metals, GMO, herbicides, the organic farming practically conserves the quality of the soil and water. There are reports mentioning that there is a huge contamination of the rivers in Europe with pesticides and they had been used several years before their detection and remain there. The environmental pollution made by pesticides, heavy metals and GMO is non reversible. Organic farming practices are sustainable, as the farmers/growers will not push nature with all its elements animals and trees/plants to produce more especially when there is a bad harvest season. Animal manure or compost are used to feed the soil and weeds are managed by rotating crops. Natural on the food label does not mean organic Many processor use various words such as Natural or Sustainable on the food label to make the consumers think that their products are organic. These foods are not certified organic foods and are full of ingredients from conventional farming which uses all these toxic chemicals starting pesticides i.e round -up to GMO and insecticides and heavy metals. We have an obligation to inform all the consumers about the huge benefits of organic foods to our health and our planet air, soil and water. Sources:

1. Human health implications of organic food and organic agriculture: a comprehensive review Environmental Health volume 16, Article number: 111 (2017) 2. Livestock antibiotics and rising temperatures disrupt soil microbial communities, Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies 3. Food Preservatives and their harmful effects, Dr Sanjay Sharma, International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications, Volume 5, Issue 4, April 2015 4. Effects of Preservatives and Emulsifiers on the Gut Microbiome By: Angel Kaufman Spring 2021 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a baccalaureate degree in Biology in cursu honorum Reviewed and approved by Dr. Jill Callahan Professor, Biology 5. Pesticides and antibiotics polluting streams across Europe, by Damian Carrington, found on https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2019/apr/08 FOS Squared introduction and commenting Organic food producers and farmers are in serious trouble. Their depedence on the organic seeds continues on the same way as their depedence on pesticides and in US on the carcinogenic GMO crops as Bayer (which bought Monsanto) enters the market. World food supply enters a global tragedy period. Organic Food Is Finally Big Food, Large Enough Monsanto Got Into It Organic food is a $120 billion industry, and while that's a tiny fraction of regular food it is large enough that companies like Chipotle and General Mills have tried to gain traction. But a large seed company? That is new. Bayer, secretly now Monsanto (as anti-science activists love to claim in their conspiracy tales), is rolling out organic-certified seeds. This is not as difficult as it sounds. To be certified organic, you only have to not use newer pesticides or genetic modification, anyone who claims they use no pesticides or genetic engineering thinks you are gullible. So GMOs can't be organic, for example, but over 2,000 products have been created using the predecessor of GMOs, Mutagenesis, and all of them can be considered organic even though they were mutated using chemical baths and radiation. You can create huge amounts of nitrogen run-off using older copper sulfate pesticides and be organic, you just can't use safe neonicotinoids. Organic industry trade group have done a terrific job. First, they got their lobbyists and trade reps on a panel inside USDA that defines what "organic" means and keeps them exempted from USDA standards. So the dozens and dozens and dozens of exemptions for synthetic products or additives while still calling yourself organic has led to a lot of products being labeled organic. Non-GMO product has over 60,000 such products even when there is no GMO version. With such a large market in places like the US and Europe, it was only a matter of time before a large company wanted a piece of that pie, and Bayer is getting in. Starting next year you can buy organically produced seeds for tomato, sweet pepper and cucumber. But don't worry, those won't say Monsanto, they will be under the Seminis and De Ruiter brands. Source: Science 2.0 Extrait d'article en Français

Les producteurs d'aliments biologiques et les agriculteurs sont en grande difficulté. Leur dépendance vis-à-vis des semences biologiques se poursuit de la même manière que leur dépendance vis-à-vis des pesticides et aux États-Unis vis-à-vis des cultures OGM cancérigènes lorsque Bayer (qui a acheté Monsanto) entre sur le marché. L'approvisionnement alimentaire mondial entre dans une période de tragédie mondiale.  Organic food is no longer a niche market. Sales of organic food products in the European Union have more than doubled over the last decade - from €16.3 billion in 2008 to €37.4 billion in 2018 - and demand continues to grow. However, many Europeans are still unsure of what "organic" really means. Is it natural? Free of pesticides? Locally grown? Well not exactly. Here are some of the conditions food products must meet in order to be considered organic in the EU: No synthetic fertilisers Natural fertilisers, such as compost and seaweed derivatives (and animal manure), are essential to maintaining fertile and healthy soil. So organic food must be grown with these products, rather than synthetic fertilisers that are used in conventional farming, and which tend to be made of harsher chemical ingredients including nitrogen compounds, phosphorus, and potassium. "Organic farming improves soil structures and quality and enhances biodiversity. Studies have shown that organic farming present 30% more of biodiversity in the fields", explains Elena Panichi, Head of Unit at DG Agriculture and Rural Development (DG AGRI). No synthetic pesticides Farmers need to fight weeds and pests. Organic farmers are only allowed to use naturally-derived pesticides, made from plants, animals, microorganisms, or minerals. "These chemicals are of a natural origin. For instance, essential oils, plant extracts, that are listed in the relevant regulation, and are authorised, following a process that implies a scientific committee to assess the effect on the environment", says Panichi. Organic farms also have techniques such as crop rotation, or planting different crops on the same plot of land, to help to prevent soil-borne diseases. Natural predators, such as ladybugs, can also be an effective method of pest control. However, it is important to remember that just because something is “natural”, it doesn’t automatically make it harmless to either people or the environment. No GMOs (No genetically modified organisms/ingredients/crops/foods/animals) To be certified as “organic”, food cannot contain products made from genetically modified crops. This rule is the same for organic meat and other livestock products. Besides, the animals are to be raised on 100% organic feed. Antibiotics as a last resort The animals we eat, or whose products we consume, need to be kept disease-free. Many conventional farmers routinely use antibiotics for disease prevention. These can end up making their way into the food chain. Excessive antibiotics are not good for people or animals because they can help create superbugs. Antimicrobial resistance is a global concern. Every year, around 33, 000 people die in the EU, due to infections from antibiotic-resistant bacteria. On organic farms, the use of antibiotics is severely restricted. Farmers control disease by limiting the number of animals they raise and using methods such as a healthy diet for their livestock. They are only allowed to use antibiotics when absolutely necessary for an animal's health, in order to avoid suffering, and when natural remedies such as phytotherapeutic and homoeopathic medicines are not effective. "If in conventional [farming], sometimes antibiotics are given as preventive tools, in organics, antibiotics can be given as a last resort if there are no other methods to intervene. Normally, the higher animal welfare standards applied in organics already keep animals in a healthier status that prevent the use of antibiotics", explains Panichi. However, studies have shown that antibiotic use on farms is on the decline. Sales of animal antibiotics in the EU have fallen by more than 34% between 2011 and 2018. Better animal welfare Organic farmers must provide the environmental conditions necessary for animals to express their natural behaviour, such as adequate outdoor space. This is not compulsory in conventional farming. There are additional rules such as the prohibition on caging or mutilation unless absolutely necessary for health reasons. What "organic" doesn't mean locally grown. Europeans are the second largest consumers of organic in the world. Local supply can’t meet demand yet, so a large number of organic products are imported. China, Ukraine, Dominican Republic and Ecuador are the main EU trade partners for organic food imports. "Green" packaging Words like “natural”, “green” or “eco” on labels and packaging do not necessarily mean a product is organic. Healthy There's a wide range of organic product on supermarket shelves, from burgers to pizzas, from cheese to wine. The health implications of consuming excess fats, salt or sugar don't disappear just because a food product is organic. Too much fat, salt and sugar is still bad for you, whether it is organic or not. How can you be sure that the “organic” food you’re buying is actually organic? The most reliable way to know if a product is organic is if it has this official EU logo. The white leaf on a green background means that EU rules on production, processing, handling and distribution, have been followed and that the product contains at least 95% organic ingredients. This logo can only be used on products that have been certified by an authorised control agency or body. Some countries have also created their own organic logos. They are optional and complementary to the EU's leaf. This is the French one, for instance. Words like “natural”, “green” or “eco” on labels and packaging do not necessarily mean a product is organic.New rules coming in 2022 EU rules on organic production will change soon. In 2022, Europe will have legislation with stricter controls. Panichi believes it will bring a "substantial improvement" to the organic sector. "We have to bear in mind that the new organic legislation is not a revolution, but it's an evolution of the organic legislation that started in the past years and has been kept evolving together with the sector". The new legislation will harmonise rules for non-EU and EU producers. It will also simplify procedures for small farms in order to attract new producers, thanks to a new system of group validation. The list of organic foods is expected to grow, with the addition of products such as salt and cork. The possibility of certifying insects as organic is also expected in the rules. What is the future of organics? "Surfaces in Europe are increasing or as well as all over the world, and they are increasing at a fast pace," says Panichi. As part of its Farm To Fork strategy, the EU has committed to increasing organic production, with the goal of 25% of all agricultural land being used for organic farming by 2030. In 2019, it was only around 8%. By 2030, Europe also aims to reduce the use of harmful chemicals and hazardous pesticides by 50%. Buying organic food is still too expensive for many. One of Farm To Fork's main goals is to make healthy, sustainable food more accessible and affordable to all Europeans. A French from 2019 shows that a basket of eight organic fruits and eight organic vegetables is, on average, twice as expensive as a basket of non-organic products. Source: Euronews Pictures: Source for Organic Leaf picture is Euronews and European Commission is for Farm to Fork picture Qu'est-ce qui rend les aliments biologiques « bio »?

Extrait d'article en Français - Pour être certifiés « biologiques », les aliments ne peuvent pas contenir de produits issus de cultures génétiquement modifiées. - Pas de pesticides de synthèse. - L'agriculture biologique améliore la structure et la qualité des sols et renforce la biodiversité. - Des mots comme « naturel », « vert » ou « éco » sur les étiquettes et les emballages ne signifient pas nécessairement qu'un produit est biologique. No additives, fewer pesticides and much more eco and animal-friendly than your average slice of bacon or jar of honey – when it comes to organic produce, there’s a lot to love. As the daughter of a beef farmer and an ambassador of Organic September’s #FeedYourHappy campaign, Sara Cox knows a thing or two about the joys of organic food. When we caught up with her she told us that she eats organic not just because “it’s gorgeous,” but because she believes that “it’s good for the animals and good for the planet,” too. “Give me a knobbly misshapen organic strawberry over the weirdly uniform non-organic ones any day,” and she’ll be happy, she says. We couldn’t agree more, to be honest, which is why we asked her to come up with a few top tips for how to #FeedYourHappy in the capital this Organic September: Get stuck in On September 16, shops across the city will be hosting all sorts of celebrations and offering free organic samples to customers. ..........have an Organic Kitchen pop-up with lots of cooking demonstrations using delicious organic ingredients going on. Guide to Organic SeptemberSpend a little, learn a lot

Catch River Cottage at Borough Market all month, delivering a season of cookery courses and free talks. Find out more info here. Go local Pop at independent pro-organic shops, ......... Or take a trip down to your local market and support organic farmers. Urban Food Fortnight – which runs from 8-24 September – showcases all the fabulous food that's produced across London. With a programme packed full of foodie events, it's a fantastic way to explore something new! Try something new Give an organic delivery box scheme a trial run. Check out companies that deliver in London, such as the Organic Delivery Company, Abel and Cole, Riverford or Well Hung Meat. A full list can be found here. Shop smart Look for the organic symbol - Soil Association or Organic Farmers & Growers - and make small changes to your weekly shopping. Take advantage of the amazing offers on your favourite organic products and stock up, or start small with your everyday essentials like milk or tea. Here's a great guide for what to look out out for. Eat up Look for organic when you eat out. There are some amazing restaurants and cafes that serve organic food. If you see the Organic Served Here logo, you can be sure they are committed to sourcing organic ingredients. The Soil Association has a fantastically comprehensive round-up of some of the capital's best pro-organic eateries. ''Sarah Cox's Guide to Organic September'' full article can be found here - Source: Foodism Farmer Angus McIntosh has the intense look of someone with a single dream like skateboarding to the South Pole. He wears a slightly ingenuous expression, as if he has just been born into a new world and finds everything curious and a bit disturbing. With a background as a trader for [...........] in London, there is a hint of cufflinks and striped shirt in his farmerish attire and smooth talk. However, his verbal spritz no longer sprouts derivatives and hedge funds but involves a passion for environmentally friendly farming. And boy do you need passion. In a world where farming is a big industry (visiting a farm in the USA is hazardous because of free floating poisons), following a dream of clean food is a kind of madness. Farmer Angus’ farm is situated on 126 hectares of irrigated pasture at Spier Wine Estate near Stellenbosch. It is a place that ignites the heart with its well cared for animals, green pastures, vegetable gardens and on site butchery. A friend calls it “fairyland”. The farm arguably hosts the Cape’s best non-industrial food production. The eggs are yolky and delicious and the meat which can be ordered online is clean and tastes like meat used to taste. Remember? Before feedlots, pesticides and hormones. About six years ago I discovered his eggs by chance, astonished by their creamy innards and thick marigold coloured yokes. Investigating their origin, I came across Farmer Angus, moving his egg laying hens in “eggmobiles” to new outdoor pasture. He told me then, “The biggest lie in agriculture is free range eggs. They live in barns, they don’t range outside. On commercial egg farms, chickens live and never leave a space equivalent to an A4 piece of paper.” And it is not only the animals that are benefitting. His egg company is now 80% owned by his staff and the eggs get better and better. “I am only a 15% shareholder but it’s got my name on it,” he says. Over the years McIntosh has developed biodynamic and regenerative agricultural practices in the raising of the farm’s animals which include cattle, pigs, chickens and laying hens, as well as vegetables and wine. His pastured livestock and poultry are moved frequently to new pastures where they can perform basic needs such as dustbathing and flapping their wings. Often in the past in butcheries or so-called organic groceries, I have asked about provenance. So far I have never met a retailer who has even taken the trouble to see where the food (particularly labelled as “organic”) they sell comes from. Farmer Angus encourages people to visit the farm and see where their food is produced. Caring for the animals properly is a high priority. More and more restaurant owners around the world are keeping their own herds for the simple reason that cared for cattle produces not only the healthiest but the tastiest meat. With farming there is so much wonkery – what irony that the salt of the earth, the food we eat is as about as full of corruption as the Zuma Cabinet. His desire is for people from all walks of life to be able to eat better and more nutritiously and to understand what they put in their bodies. [...................] The challenge of agricultural sustainability has become more intense in recent years with climate change, water scarcity, degradation of ecosystem services and biodiversity, the sharp rise in the cost of food, agricultural inputs and energy, as well as the financial crisis hitting hard on South Africa. He reels off stats with an almost cult-like enthusiasm. “A well looked after Jersey cow that has grown up on pasture should give you 50 lactations. Do you know what the average lactation in South Africa is? Two point one. They are treated as monogastrics and fed a heavy corn diet three times a day. As a result the milk is so high in pus that they are forced to homogenise it. “Of course people are going to be allergic to it.”

I have always wondered why so many people are “allergic to dairy”. South Africa should be the land of milk and honey; instead it is the land of cheap chemicalised food. “We have the highest obesity rate in the world. The rural Africans understood the value of milk, a whole food, but they lost the tradition when they came to the cities to work.” Personally, says Farmer Angus, “I think that consumers have to think about food differently and eat differently. They need to be conscious that behind a kilo of tomatoes lies a lot of work. They need to know where their food comes from and what goes into it. “People are living on more and more processed foods, so the body is craving nutrients. The only thing that the people in agriculture agree on is that the nutrient content of food has been in decline for 120 years. The carrots your grandmother ate and the ones you eat might look the same but on a nutritional level they are entirely different. “Most of us can grow our own vegetables, we can all make our own worm compost which is the best fertiliser of all. South Africa has got a million unemployed people. Why are they not growing their own food? Here’s why. There is a stigma attached to farmers which is why so few guys grow their own food in a place like Khayelitsha. They want to wear zoot suits and drive Beemers.” McIntosh’s new project is producing first grade grass fed, pesticide free food at an affordable price. Last week, wandering the aisles of Checkers, I came across such usually unaffordable products as pancetta, coppa, prosciutto at a price within my budget. Let us give thanks for the pig. Pancetta made from the belly, coppa from the neck and prosciutto from the leg and Black Forest ham to die for from the loin, a real feast. But not a feast for pigs, especially in South Africa. “I only know two farmers who do not cage their pigs,” says McIntosh. The European Parliament’s Agriculture Committee has recently called on the European Commission to propose a revision of the EU directive on farmed animals with the objective of phasing out the use of cages in animal farming. McIntosh’s move to supermarket selling is not only significant because people like me can afford to buy it but it is the first time that grass-fed beef is being sold at the same price as feedlot products. “But more important,” says Farmer Angus, “this is a truly costed item. The beef you buy in a shop is not really costed, the antibiotic resistance is not costed, the inflammatory diseases you get are not costed. There is a whole lot of stuff that is not in the price, so true cost accounting is another thing that has to be on the table in order to keep any ethical enterprise going.” “This stuff has been outdoors reared, it is not imported and most important it has been cured without adding nitrates or nitrites plus the chemical arsenal that fires up most commercial foods. Our charcuterie, made by Gastro Foods, is the only charcuterie in South Africa cured without added nitrates or nitrites. “We have the space, we have the weather, all we need is the absolute desire for better nutrition. “And there are rewards. The carbon in our soil has increased and we get paid credit for that. What people don’t realise is that the vegan diet that everyone is trying to ram down our throats is destructive to the ecology. Whereas this is generative to the ecology. In the vegan utopia there are no animals, so how do they make the food for the plants? They can’t make animal based fertiliser or compost so they have to use chemicals. “Actually, we have no choice. We go the ethical route or we die.” As Joel Saliton, a farmer in the USA famous for his ethical practices, says, “If you think organic food is expensive, try cancer.” A study 2020 conducted by the insurance comparison website Compare The Market, which ranked the healthiest and unhealthiest countries – all part of the Organisation for Economic and Co-operation Development, found that South Africa is the “unhealthiest country in the world”. A separate study, The Indigo Wellness Index, which tracks the health and wellness status of 151 countries, also found South Africans were dangerously unhealthy and ranked SA the unhealthiest country in the world in 2019. Meanwhile, in 2016, the World Health Organisation (WHO) estimated 28.3% of adults in South Africa were obese. This was the highest obesity rate for the sub-Saharan African countries recorded by the WHO. Source: dailymaverick Organic Farming lessens reliance on Pesticides and promotes Public Health by lowering Dietary Risks13/7/2021

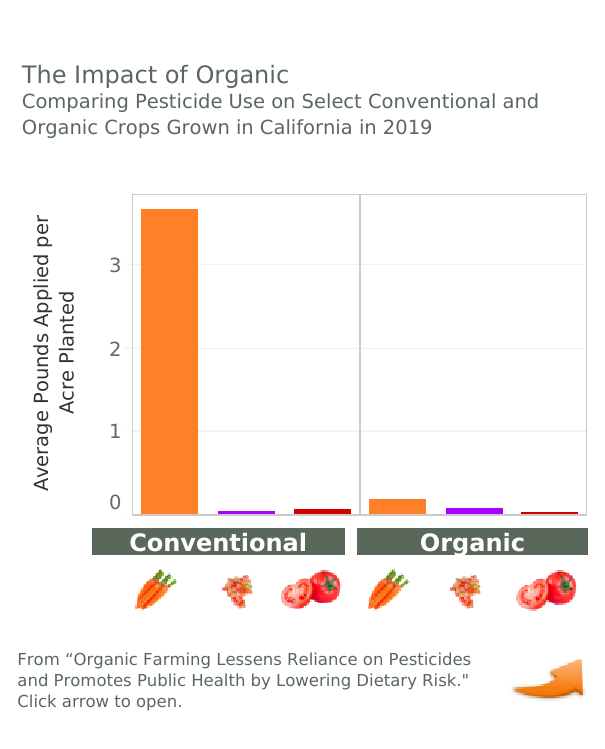

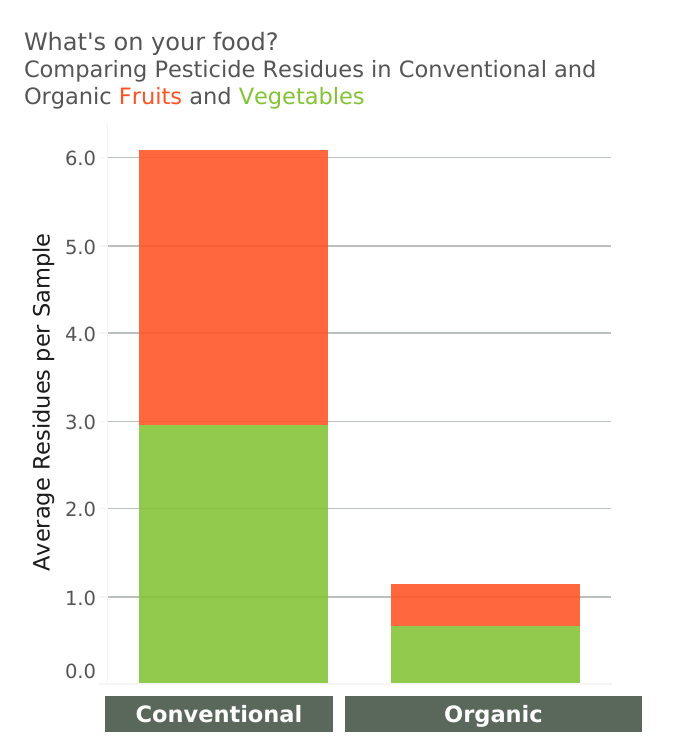

Did you know there are pesticide residues in and on your food on a daily basis (unless you seek out and consume mostly organic food)? Pesticides include insecticides, herbicides, fungicides, fumigants, and plant growth regulators. These chemicals can be taken up by crops and some make their way to your kitchen table. We have all heard the saying “you are what you eat.” Yet a question lingers largely unanswered — What are the chemicals in the food we eat doing to our bodies, our health, and the integrity of the human genome (i.e. the DNA in our genes)? Cutting-edge research has begun to shed new and brighter light on the ways pesticide exposure can contribute to or cause adverse health outcomes. Pesticide exposures (from conventional food) have been linked to multiple health problems including - Cancer, - Getting and staying pregnant, - Developmental delays in children, - Heritable genetic changes, - Altered gut health, - Neurological disorders like Parkinson’s disease, and other chronic health problems. Clearly, pesticides can adversely impact the brain and our neurological system, the human immune system, and our reproductive health. Neurological impacts increase the risk of autism, ADHD, bad behavior, and can reduce IQ and hasten mental decline among the elderly. Anything that impairs the functioning of the immune system increases the risk of cancer, serious infections, and can worsen viral pandemics, as we have regretfully learned throughout the Covid-19 outbreak. Several pesticides have been shown to cause or contribute to infertility, spontaneous abortion, and a range of birth defects and metabolic problems in newborns and children as they grow up. So how do we avoid potentially harmful pesticide exposures? In the USA in 2021, the surest way to minimize pesticide dietary exposure and health risks is to consume organically grown food. How do we know? We have run the numbers. A recently-published HHRA paper, written by a team led by the HHRA Executive Director Chuck Benbrook, draws on multiple state and federal data sources in comparing the dietary risks stemming from pesticide residues in organic vs conventionally grown foods. The new paper is entitled “Organic Farming Lessens Reliance on Pesticides and Promotes Public Health by Lowering Dietary Risks”, and was published by the European journal Agronomy. Benbrook was joined by co-authors Dr. Susan Kegley and Dr. Brian Baker in conducting the research reported in the paper. There is good news in the paper’s many data-heavy tables. Organic farms use pesticides far less often and less intensively than on nearby conventional farms growing the same crop (see the chart below for an example from California). On organic farms, pesticides are an infrequently used tool, applied only when needed and after a variety of other control methods have been deployed. Plus, only a small subset of currently registered pesticides can be used on organic farms – just 91 active ingredients are approved for organic use, compared to the 1,200 available to conventional farmers. Pesticides approved by the USDA’s National Organic Program (NOP) are typically exempt from the requirement for a tolerance set by the EPA because they possess no, or very low, toxicity. NOP-approved pesticides cannot contain toxic, synthetic additives or active ingredients. Many of them are familiar household products, like soap, vinegar, clove oil, and rubbing alcohol. On many conventional farms, pesticides are the primary, or even sole tool used by farmers to avoid costly damage to crops by pests. Conventional farmers also have far more pesticide choices. The products registered for many crops include known toxic and high-risk chemicals linked to a number of adverse health outcomes. More good news — choosing and consuming organic food, especially fruits and vegetables, can largely eliminate the risks posed by pesticide dietary exposure (see figure below). In general, the residues of any given pesticide in organic samples are usually markedly lower than the same residue in conventional samples. This is important because pesticide residues in fruit and vegetable products account for well over 95% of overall pesticide dietary risks across the entire food supply. The pesticide-risk reduction benefits of organic farming now extend to a little over 10% of the nation’s fruit and vegetable supply. Impacts on the farm and farmers. While the dietary risks from pesticide use on organic farms compared to conventional farms is the focus of the Agronomy paper, the consequences of heavy reliance on pesticides by many conventional farms are also discussed. These include the emergence and spread of resistant weeds, insects, and plant pathogens that then require farmers to spray more pesticides, more often, and sometimes at higher rates – this is known as the herbicide treadmill. The heavy reliance on pesticides on conventional farms also can impair soil health and degrade water quality. It can undermine both above and below-ground biodiversity, and in some areas has decimated populations of insects and other organisms, including pollinators, birds, and fish. People applying pesticides and people working in or near treated fields are the most heavily exposed and face the highest risks. A grower’s choices in knitting together an Integrated Pest Management (IPM) system impacts workers, consumers, and the environment. Organic farmers rely on biological, cultural, and other non-chemical methods in their prevention-based IPM systems and generally succeed in keeping pests in check. Switching from conventional farming to organic production takes time and requires new skills and tactics. Most farmers who have made the change have done so mostly on their own. Other organic farmers and their pest control advisors remain the primary source of technical support and encouragement for neighboring farmers thinking about taking the plunge. The authors end the paper with a review of concrete actions, policy changes, and investments needed to support those willing to make the transition to organic. First, “organic farmers need better access to packing, processing and storage facilities linked into wholesale and retail supply chains.” In fact, many farmers hesitate to transition to organic not because of problems adhering to organic farming methods or controlling pests, but because of a lack of marketing opportunities. Second, agribusiness firms have shown little interest in developing and manufacturing the specialized tools and inputs needed by organic farmers. There are many unmet needs. Tillage and cultivation equipment suitable for small-scale operations is hard to come by, unless imported from Europe. Infrastructure investments are needed to increase the supply and quality, and lower the cost of compost and other soil amendments. More cost-effective ways are needed for organic farmers — and indeed all farmers — to rely on insect pheromones in disrupting mating and microbial biopesticides that control pests by disrupting their development, reproduction, or metabolism. Third and perhaps most important is “public education and access to information about the significant health, environmental, animal welfare, farmer, and worker benefits that arise when conventional growers successfully switch to organic farming.” The case for transitioning most of the approximate 1.2% of US cropland growing fruits and vegetables to organic is strong and bound to grow more compelling. The paper points out that the technology and systems exist to rapidly increase the organic share of fruit and vegetable production from a little over 10% today to over 70% in five to 10 years. The only thing holding back growers is the lack of demand. As more farmers switch to organic, more investment in tools, technology, infrastructure, and human skills will bring to organic food supply chains the same economies of scale that now make conventional produce so affordable. As a result, over time the organic price premium will narrow as the supply of organic produce expands. Organic farming reduces pesticide reliance and dramatically reduces dietary risk. The opportunity to promote healthy pregnancies and thriving newborns via farming system changes will join the need to build soil health and combat climate change in driving new investments and policy changes that will hopefully support farmers open to innovation and willing to transition to organic. Source: Heartland Health Research Alliance webpage |

Archives

January 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed